My Black Angel & Ana Mendieta

“I have been carrying on a dialogue between the landscape and the female body (based on my own silhouette). I believe this has been a direct result of my having been torn from my homeland (Cuba) during my adolescence. I am overwhelmed by the feeling of having been cast from the womb (nature). My art is … a return to the maternal source. Through my earth/body sculptures I become one with the earth…. I become an extension of nature and nature becomes an extension of my body.” –Ana Mendieta

In 1961, as part of a covert U.S. government action called Operation Peter Pan, twelve-year-old Ana Mendieta and her older sister were flown from Havana to Dubuque, Iowa. In all, 14,000 Cuban children were evacuated in response to their parents’ fears of Fidel Castro’s Communist regime. The sisters were lodged at St. Mary’s Orphan Home[1] in Dubuque and then, for the next four years, were shuttled between foster homes in Cedar Rapids until Ana graduated from Regis High School. She studied at the University of Iowa from 1969 to 1977, earning two master’s degrees and jump-starting her career as a ground-breaking multimedia performance artist. One of her performances would happen at a locally famous site in Iowa City’s Oakland Cemetery.

This year, on the last night of August, as a crescent moon was rising on the eastern horizon, my friend and I walked one block from her house on Brown Street into that cemetery. We commented on how dark it had suddenly become – no streetlights, no house lights, no headlights, and large trees blocking out the city around us. We were soon engulfed by the sonorous call-and-response of a choir of tree frogs. Walking deeper into the cemetery, we could see a glimmer in the distance. As we approached the light, we realized it was a lamppost illuminating the Black Angel, likely placed there by cemetery staff to discourage acts of vandalism or bacchanalian gatherings.

The Black Angel is a popular attraction, a statue commissioned by a mother to look down on the grave of her son, who died at the age of eighteen. To the left of the angel stands his headstone, a sculpture of a ragged tree stump with an ax head buried in it to symbolize a life cut short.[2] The unusual color of the angel, combined with the overactive imaginations and superstitious tendencies of college students, has led to a plethora of urban legends about curses of all types, which enwrap the statue in a patina of mystery and might explain the offerings left at its feet.[3]

I’ve walked and biked past the Black Angel many times. When I arrived in Iowa City in 1975, my first apartment was two blocks away on Reno Street; then in the 1990s, I would bike by it on a shortcut from my home on the east side of town to my job on the north side. I’ve admired it, studied it, but always respectfully kept my distance. It is rather foreboding – the angel, her enormous wings raised, towers thirteen feet above ground level and has been blackened by the natural oxidation process of the bronze.

But that night I felt emboldened, perhaps because my friend was with me, perhaps because no one else was in the cemetery. I climbed atop the four-foot-tall pedestal, using the tree stump gravestone to give me a boost. I sidestepped the day’s offerings and, with little room to do anything else, looked up at the Black Angel and hugged her around the waist. I never realized how attractive she is. Her long sheer gown clings, revealing the figure of a young woman. When viewed at ground level, her facial features are enshrouded by hair that hangs down around her face. But from my vantage point, I could, for the first time, see her face clearly. Although her eyes were closed, I felt her tenderly looking down at me. Some artistic vandal had smeared her lips with red lipstick, which somehow made her look more beautiful. Graffiti had been scratched into the bronze of her upper torso, but the accretion of patina was slowly obscuring those marks. A swarm of paper wasps had built a nest in her left armpit. Smitten, I hugged her longer than seemed proper, and then carefully climbed down.

The Czech Bohemian woman who commissioned this statue,[4] Teresa Doležal Feldevert, immigrated with her son, Eddie, to the nearby Goosetown neighborhood in 1878 and found work as a midwife. After Eddie’s death in 1891, she moved from city to city, eventually settling in Eugene, Oregon, and remarrying. When this husband died, Teresa inherited his cattle ranch and used some of her wealth to build this monument. On the base of the statue, beneath the raised letters “Rodina Feldevertova,”[5] are engraved “Nicholas Feldevert 1825–1911” and “Teresa Feldevert 1836–” They are buried beneath the large stone slab that extends in front of the sculpture. She died in 1924, but no one was left to add her end date.

In 1975, Ana Mendieta, performed one of the early iterations of her earth/body sculpture series Siluetas[6] at the Black Angel site. According to Jane Blocker,[7] Mendieta filmed herself lying face down on the stone slab, arms outstretched, dressed in black, then rising to sprinkle handfuls of black pigment powder to form a body outline, adding a pile of red pigment powder in the area of her heart and a large black X over the entire silhouette, and finally looking directly at the Black Angel and swinging her leg in a wide arc to sweep away the silhouette. We can offer many interpretations of this performance: an act of commemoration, an identification with maternal grief and the immigrant’s pain of displacement, a ritualistic enactment of death and rebirth, a healing ceremony. Perhaps it was all of these, and more.

My friend and I continued our walk. We headed back toward her house, taking a different route, picking our way through an unfamiliar corner of the cemetery that borders Church Street. The large oaks, hickories, and pines intensified the darkness. The nineteenth-century gravestones leaned off-kilter, rimed with lichen. At one point, I came to a stone border that demarcated a narrow paved lane no longer in use as a cemetery entrance. I looked down in the dark and estimated that the lane was at most a foot below where I stood. As I stepped down, I realized I had gravely misjudged the distance and was stepping into air, unsure when I would land. I was falling, but it felt like slow motion, like an unseen hand had reached out to help me down.

When I was a child, one of the few framed artworks in our house was a small reproduction that depicted a guardian angel hovering over a boy and girl at play unaware of their proximity to a precipice. The scene gave my mother some reassurance as she sent the ten of us out to play beyond her reach and sight. The actual distance of that step down was three feet. I tipped forward, breaking my landing with my hands and right knee, while my left ankle scraped against that stone border. My friend said I just disappeared from sight in front of her. That misstep earned me a few scrapes, but no blood, no broken bones, not even a bruise. Some might say my fall was the Black Angel avenging the liberties I had taken with her. I prefer to think she was protecting me.

On September 8, 1985, the Cuban-American feminist artist Ana Mendieta fell to her death from her 34th-floor apartment in Greenwich Village. Many believed she was pushed, whether intentionally or accidentally, by her husband, the artist Carl Andre, in the midst of a heated argument. I want to believe an angel was with her, perhaps not to save her but at least to hold her hand as she flew to the earth, filling her with peace in that last moment of her life.

Footnotes:

[1] Run by Sisters of the Third Order of St. Francis, the facility shifted its mission in the 1960s to serving “hard to care for children.”

[2] The last three lines of the headstone’s inscription: “I was not granted time to bid adieu / Do not weep for me dear mother / I am at peace in my cool grave.”

[3] Such as Norway spruce cones, a pair of tea roses, a guitar pick, a beaded star brooch, a couple of dollars folded under a piece of pink quartz, small piles of quarters and pennies, and two unexpired credit cards!

[4] The sculptor was a Czech-American artist, Mario Korbel, who also sculpted the Alma Mater statue located at the entrance to the Universidad de La Habana, which young Ana Mendieta may have seen.

[5] Czech for “The Family Feldevert.”

[6] The Stanley Museum of Art is now showing a piece of hers documenting three other Siluetas, as well as two films she made during her years in Iowa City.

[7] See her essay “The Black Angel: Ana Mendieta in Iowa City,” published in The Latino/a Midwest Reader, University of Illinois Press, 2017.

Rough Carpenter (Jobs of My Youth #3)

Mike, Jon, me, and Brother Ralph standing in front of the modular home factory we helped build

“It’s not just that you’re an adolescent at the end of your teens, but that adulthood, a category into which we put everyone who is not a child, is a constantly changing condition; it’s as though we didn’t note that the long shadows at sunrise and the dew of morning are different than the flat, clear light of noon when we call it all daytime. You change, if you’re lucky, strengthen yourself and your purpose over time; at best you are gaining orientation and clarity, in which something that might be ripeness and calm is filling in where the naïveté and urgency of youth are seeping away.” –Rebecca Solnit, Recollections of My Nonexistence

When my county road crew gig wrapped up at the end of the summer, I got ready to start my next job, one for which I received no financial compensation. In the last semester of my senior year, I decided to postpone college and commit to doing volunteer work with my classmates Jon and Mike for a Catholic order called Glenmary Home Missioners. Although I attended a college prep high school, I don’t remember anyone from the counselors office asking me about my college plans, and my parents never broached the subject.[1] Maybe this lack of initiative on my part indicated I wasn’t ready to make that step. In any case, when I heard about Jon and Mike’s plan to take what is now called a gap year, I jumped at the chance to join them. By September 1972, we were driving east on the Penn Turnpike toward McConnellsburg, a south-central Pennsylvania borough located in Big Cove Valley, amidst the Ridge and Valley section of the Appalachians. We were on our way to help out with Glenmary’s Project HOPE (Homes On People’s Energy).

More precisely, we were helping Brother Ralph build homes for and with the families that lived on The Ridge, a segregated Black community located a mile outside of town. Brother Ralph became our mentor and friend. Raised on a farm in southern Indiana, he was a man of saintly simplicity, as easy-going and tender-hearted as they come. One of our favorite interchanges went something like this: Ralph would be kidding one of us about something. We’d say, “Brother Ralph, are you making fun of me?” He’d reply with a chuckle, “Shucks, I can’t make fun of you – the fun’s already there.” We never tired of that joke.

Brother Ralph was a skilled master builder. Thanks to his patient guidance, we learned how to lay cinder block, drive a sixteen-penny nail, toenail a rafter beam into place, mud sheetrock, install windows, doors, and electrical outlets. We experienced the exhilaration of nailing together the two-by-fours that became the frame of an exterior wall and then raising it, the four of us together, into place.

I enjoyed the construction work – the pleasures of learning the craft and using what I learned to build something as essential as a home. I also enjoyed building friendships with the tight-knit group of families on The Ridge. That fall we sometimes lent a hand to a local roofing outfit run by Bob Wolford and Harvey Kneese. They were funneling their roofing business profits into a project to build a modular home factory. The agreement was that, in exchange for our donated labor, Bob and Harvey would offer discounted rates to families on The Ridge who wanted to buy one of their homes.

Jon, Mike, and I helped them replace a few lovely old gray slate roofs with asphalt shingles. They didn’t let us up on those high steep-pitched roofs, but we’d serve as the ground crew, tossing the pieces of slate into a dump truck, lugging packets of shingles up the ladder to the crew. We also spent a couple of beautiful autumn days on the low-pitched roof of an auto dealership on Lincoln Way[2] at the east edge of town, preparing the roof for fresh shingles by prying up the old ones with roofing spades. We would occasionally stop, take a deep breath and a long swig of water, stretching our aching backs as we looked east to the wooded slopes of Tuscarora Mountain or west toward town and Sheep Meadow Mountain beyond. Then we’d get back to it.

Our nine-month stint in McConnellsburg was not all work. Brother Al Behm, director of Glenmary’s volunteer program, occasionally visited us. Late that fall, the four of us drove to Glenmary’s retreat house and youth center in Fairfield, Connecticut, for the weekend. He engaged us in some deep discussions about “life’s big questions.”[3] And I got my first taste of Manhattan when we took the train down to the city. We caught the newly released movie Sounder, featuring the great actor Cicely Tyson and a soundtrack by Taj Mahal, and saw our first Broadway play, Joseph Papp’s production of Two Gentleman of Verona.

By late fall, the six of us – Bob, Harvey, Brother Ralph, Jon, Mike, and I – had begun constructing a 50-by-100-foot sheet-metal building in a sheep pasture on a wind-bitten hillside west of town. When the site was being leveled and dirt needed to be moved, I learned how to use a stick shift ... while learning how to drive a dump truck, pretty much killing that transmission.

I gained respect for any construction work done outdoors in the winter. Because of the need for precision when framing a steel building and the unforgiving nature of that material, we did a lot of standing around before we wrestled a steel column into the bolts of a concrete pier or persuaded two roof trusses to meet at the ridge with the help of a log loader. Handling the steel was miserably cold work – I had not yet learned the perfect practicality of Carhartt coveralls.

By March we were helping to construct the first modular home, its two halves efficiently built side-by-side on flatbed platforms that would then be hauled out through the large sliding doors by semi trucks. And not long after that, we were back on The Ridge, putting the finishing touches on a sturdy two-story house for Bebe and her four kids, painting the interior and exterior walls, installing cabinets and sinks and toilets, laying carpet and linoleum flooring, and replacing the temporary cinder block steps with an inviting front porch. When Bebe and her family moved in, we joined the rest of The Ridge in a huge housewarming potluck. Bebe, the tough matriarch who rarely cracked a smile when she worked alongside us on the house, could barely stop beaming.

By the end of May, Jon, Mike, and I[4] were saying goodbye to Brother Ralph, our friends on The Ridge, our second-floor apartment overlooking Lincoln Way. We were driving home in the blue 1952 Chevy Impala that Ralph had used to transport us all to work sites and then sold to me for one dollar. The tail fins of that Impala felt like wings slicing through air as we drove west toward Ohio and the next chapter of our lives.

Footnotes:

[1] My father had gone to Marquette University on the GI Bill after World War II, my mother never attended college, and they were probably too busy raising my younger nine siblings to think much about this.

[2] U.S. Route 30, also known as the Lincoln Highway, which follows the route of the 18th-century Philadelphia-to-Pittsburgh Turnpike.

[3] The following year, Brother Al included two of my poems in his 12-page booklet titled “I Never Met a Bad One,” which began “...but I have met some of you who have been confused, looking for the thing that will make you happy, and that doesn't always mean what feels good.”

[4] By then, we were known around town as “the church boys.”

Road Worker (Jobs of My Youth #2)

Four Brothers, Hudson, Ohio, 4 June 1972

“You are in your youth walking down a long road that will branch and branch again, and your life is full of choices with huge and unpredictable consequences, and you rarely get to come back to choose the other route. You are making something, a life, a self, and it is an intensely creative task as well as one at which it is more than possible to fail, a little, a lot, miserably, fatally. Youth is a high-risk business.” –Rebecca Solnit, Recollections of My Nonexistence

The words happen and happy both derive from the same Old Norse word, happ, meaning “good luck.” I sometimes reflect on how my life has unfolded, and the relationship between what has happened to me and my happiness. I know the latter had something to do with luck but also with finding a measure of contentment among those “simple twists of fate.”

The photograph introducing this piece is worth an explanation. This portrait of brothers – from left to right, Jon, Jim, me, Michael – was taken at Jim’s home the evening of our high school graduation. We were basking in the warmth of our friendship and the spotlight of our achievements. Jim shared the photo with the three of us at the recent reunion of the Walsh Jesuit High School Class of ’72. Studying this fifty-year-old photo, one can almost foresee the trajectories of our lives.

Jon – in my opinion, the leader of our class – instead of facing the photographer, turns to the rest of us, more interested in our reactions to the moment, already preparing to become the empathetic school psychologist. Jim offers his wonderfully engaging smile. He would eventually apply his gregariousness, love of global travel, and facility with languages to a career with Rail Europe. His signature lighthearted chuckle often punctuates things he’s said, part amused by his statement, part sheepish about his amusement. Michael, at first blush a ball of red-haired energy, is an unexpectedly gentle and soft-spoken man. We are both introverts, writers, poets, who for portions of our lives shared our love of literature with students, Michael at the college level, me at the high school level.

We were fully aware that we stood on the cusps of our lives. Behind our good front of bravado and self-confidence, something else was brewing. One only need notice what we were doing with our hands – well, not Jon’s self-assured cowboy pose, thumbs tucked in his belt, but the hands in pockets, hands in fig-leaf pose, crossed arms – to see that we were unconsciously signaling our understandable anxiety about the future.

Within a week of graduation, I started a job working for the Summit County Roads Department, tending the roadways in rural Twinsburg Township, north of Hudson and east of what would later become the Cuyahoga Valley National Park. I had my father to thank for this government job. He was a liquor salesman, which meant he spent his workdays schmoozing the owners and bartenders of one restaurant or tavern after another. His goal was to persuade those people to put his brands in the well, but he knew the best way to do that was by building relationships. He truly enjoyed getting to know people, telling stories and jokes, talking with them about their businesses. Through all this, he developed the kind of connections that could land me a summer job taking care of the county’s roads.

This was my first time working on a crew. The road maintenance garage we worked out of was home to a dozen full-time workers. I quickly learned who the chiefs were and the pecking order of the rest of the outfit, an order decided mostly by seniority but to some extent by charisma. I was one of three summertime workers, but the only rookie, the others being college students returning for their second or third season. I did what any newbie should do – watched, listened, took mental notes, put up with teasing that seemed a kind of initiation, and learned how to fit in. I dutifully laughed at the jokes, sensing from the reactions of others that they’d all heard the punchlines before.

Road work is manual labor of course, at times physically demanding, and I sometimes finished a shift exhausted. But I followed the lead of the full-timers, who showed me how to pace myself, and reminded me with their looks that I would gain nothing by showing them up with my youthful energy and enthusiasm. I was grateful for these tips; certain members of the crew took me under their wings in a way that felt paternal or at least avuncular. I learned how to handle the scythes and beat-up mowers we used to trim the grass around guardrails. I learned how to wield a wide-scoop shovel, reaching into the back of the bright orange dump truck for a shovel-load of gravel and slinging it so it spread evenly over fresh tar. I also learned how to lean on that shovel so it looked like I was doing something when there was nothing to do.

This was also my first time punching a time clock. Punctuality was required; I was no longer a high school student, and being late resulted in harsher consequences than a frown from one’s teacher. I’d punch in and then join the crew, who would invariably loll around sipping bad coffee and swapping stories for a half-hour before we hopped in the trucks and headed off to some work site. There was a side benefit to this job: One of the other summer workers was dealing a little pot on the side. A few times that summer, we’d slip away near the end of lunch and meet at his car so I could buy an ounce from him, something the full-timers would’ve never condoned.

During those three months in the employ of the county, “chipping up rocks for the great highway,” I came to appreciate the pleasure of doing a hard day’s work. I took a particular pride in the muscle-tiredness from eight hours of manual labor, the tan lines of being outdoors, and the calluses of working with my hands. I was also given a glimpse into the mind-numbing routines of such work and how it could wear on a body over a lifetime.

Paperboy (Jobs of My Youth #1)

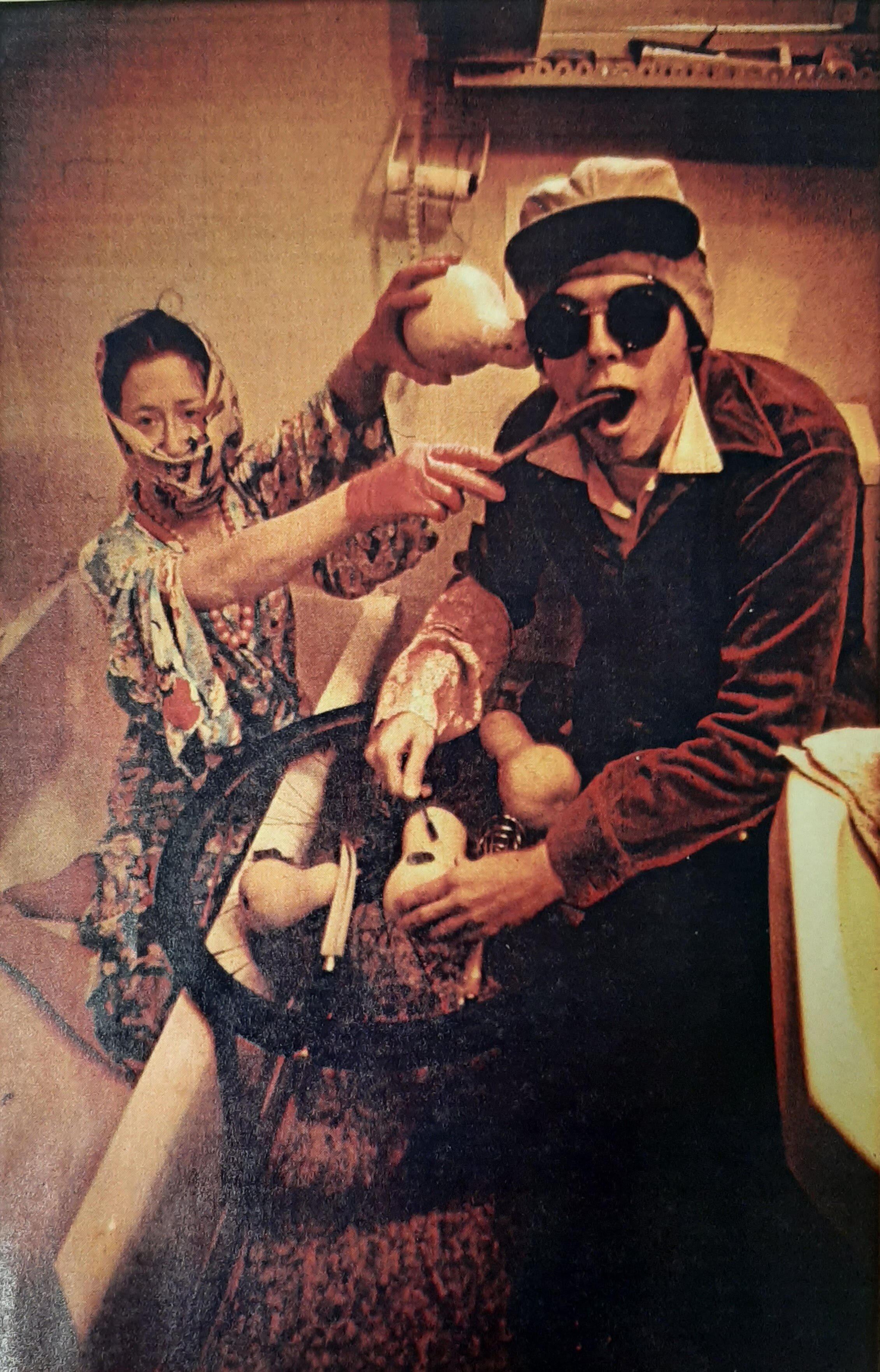

One of my favorite jobs from the early 1980s - apprentice printer at Coffee House Press. Me on the left getting ready to ink the clamshell platen press, Allan Kornblum on the right running the ATF Little Giant flatbed cylinder press.

A week ago, my neighbor Loren stopped by to ask if I could lend him and his cousin Quentin a hand with pouring a backyard patio slab. I said I’d be glad to. So, early Monday morning, as a concrete mixer chugged up our quiet side street, I finished my bowl of granola and hustled over to his house. I was the youngest guy on our crew, so I wheelbarrowed the concrete from the mixer on the street to the slab form behind the house. Loren pointed where to drop each load as they adjusted the rebar and leveled the surface with a two-by-four screed. The work brought back memories of my days as a hod carrier for a brick crew in Butler County, Kentucky, and other honest labor I’ve performed for hire. I began to write about jobs I’ve held, hoping for more than a pleasant swim through nostalgia, hoping to get at what the work taught me.

In 1964, at the age of ten, I landed my first job. My friend Mike Keller had signed up for an Akron Beacon Journal paper route and asked if I’d like to help him. He had ninety customers, so it would’ve been a challenge for one kid, especially on Wednesdays. Loaded with advertising inserts, the Wednesday paper was so big I could barely fit thirty in my canvas bag, carrying the last fifteen in a precarious stack atop them. I’d put the strap of the paper bag on my head and lug the load that way, leaning forward a bit as I walked, reaching under my left arm to pull out a paper when I got to a house. Except for Sunday’s six a.m. edition, it was an afternoon paper. After school, I’d pick up my papers at a pallet near Kent Road, where the bundles for four other routes would be dropped off. Across the street, a drugstore with a soda fountain was our refuge if the Beacon Journal truck was late. We’d sip vanilla or cherry phosphates while keeping an eye out for the truck from our swivel seats.

Before long, Mike and I lucked out when a condominium apartment complex, Silver Lake Towers, was built within the boundaries of our route, doubling the number of customers. Mike decided to divide the route in two. No surprise, he took the condominiums, leaving me the rest – a few apartments on Kent Road, then Sycamore Drive, Gorge Park Boulevard past the cemetery, Patty Ann Drive, Lake Road, and up and down Englewood Drive. I was able to arrange the route so I finished just a few minutes from home. I got used to the routine of delivering the news, rain or shine, in the snow of winter and the heat of summer.

On days when the edition was smaller and the weather was favorable, I developed the skill of folding the newspaper – holding the paper so the fold pointed up, slipping my index finger into the center of the left edge of the paper, folding over the first two inches of the right side of the paper, folding that again, then tucking the folded right half of the paper into the center of its left edge. I could fling a properly folded paper twenty feet without it opening in mid-flight, and land it softly on the porch, right at the front door.

A few customers took care of their bill through the office, but most paid me. Some paid four or five weeks at a time, but more paid me weekly. I’d collect on Saturday mornings, knocking on doors, getting to know my customers – the Greenwalds, Domingos, Wynns, Huscrofts, Mariolas, Cardones, Rubels. During most of my paperboy career, from 1964 to the fall of 1969, the cost for a weekly subscription was sixty cents. Folks would hand me a dollar, and I’d reach down to the coin dispenser hooked to my belt – ching, ching, ching, quarter, nickel, dime – and hand them their change. I’d stop halfway at Isaly’s, a diner and ice cream shop on Kent Road, to sit in a booth and treat myself to lunch while I updated my books. I was a bona fide businessperson.

I paid my bill once a month. The district manager would meet up with the paperboys in the basement of a church on Graham Road. We paid him in cash. What was left over was profit, and I was able to save enough to pay my tuition at Walsh Jesuit High School.[1] For the most part, I liked my customers, and they liked me. One customer on Gorge Park, Mr. Taylor, ran a ceramics studio out of his basement and began to hire me to do odd jobs. Besides clay mixers and kilns, his basement was filled with endless shelves of ceramic molds. People would take classes there, learning to paint, glaze, and fire sugar bowls, coffee mugs, vases, statues of cats with long eyelashes, all manner of dust-collecting bric-a-brac. When I handed down my route to my brothers Joe and Tom, I started working for him regularly, raking endless piles of leaves in the fall, sweeping out his studio, unloading pottery molds and large bricks of earthenware clay, loading boxes of ceramic pottery into customers’ cars.

By this time, I had also started caddying (or as we called it, looping) at Silver Lake Country Club. The country club was only a mile and a half from my house but a far greater distance by income bracket. I looped for lawyers and doctors and investment bankers – the upper crust. You wanted to caddy for golfers who hit the ball long and straight, who actually enjoyed their time on the golf course, who didn’t drink during their round or throw their putter at you when they missed a tap-in, who tipped well – that was a rare combination. I sometimes crept onto the course late at night and swam around in the water hazards, salvaging the expensive Titleists the duffers I’d caddied for, whose hubris lent them an unreasonably high regard for their golfing prowess, had deposited there.

The caddy shack was another milieu entirely. Most of the loopers were older than me – guys in their twenties who would loop a double (carry two bags) before lunch and then take another eighteen-hole loop in the heat of the afternoon. I tried to steer clear of these guys – they viewed younger kids like me as fresh meat – and never joined their card games, where a day’s wages could be lost in the blink of an eye. One reason I caddied was that it gave me the privilege of playing the course for free on Mondays, when it was closed to the public. But more importantly, looping at the country club allowed me to appraise the world hidden behind the facade of those expensive homes and expansive lawns I biked past on my way to Silver Lake to go fishing.

Overall, I grew to appreciate the rhythms of working, the discipline it required, the camaraderie it offered. I wore with honor the newsprint ink that covered my hands after delivering papers, agreeing with Van Morrison’s sentiments about work: “What’s my line? I’m happy cleaning windows.”

Footnote:

[1] I was a “scholarship boy” my first year. (Entering its fourth year of operation, the school freely distributed scholarships to recruit students.) The tuition the next year was $350, increasing to $700 by my senior year.

Finding a Way Home: On Homelessness

My son Jesse and me in Austin, Thanksgiving 2019.

Friday, June 17, one moment in a sixteen-day road trip I’ve just returned from, some tame version of the journeys of my late teens and early twenties. Even in those days, for all the pleasure I took from the act of vagabonding and hitchhiking, of going where the climate suited my clothes, I appreciated the value of home, which by the time I turned twenty-two had become Iowa City.

On this trip taken in my sixth-eighth year, I was always able to make a temporary home somewhere – in Louisville, the home of my girlfriend’s brother and sister-in-law; in Roanoke, the home of my daughter and two grandsons; in the Long Island town of Centerport, the home of my high school girlfriend and her husband; in Columbus, Ohio, the home of one of my sisters. In all these places, I was blessed with the comfort and security that home represents.

Lately, I’ve been troubled by a world that forces some to live without that comfort and security. In the last fifty years, the withering of government funding for social services, mental health care, substance abuse programs, and low-income housing has resulted in the tragic fact that over a half-million Americans now experience homelessness every night. In March, I watched a documentary film, Lead Me Home,[1] that introduced me to those who reckon daily with housing insecurity, and with the arbitrary twists of fate that landed them in such circumstances.

As I watched the film, I kept thinking about my youngest son, Jesse, who recently lost his home and is living on the streets of Austin, Texas. A talented cook, he began to suffer from bipolar disorder in his early twenties while living and working in New York City. His condition undiagnosed, he self-medicated the extreme mood swings, which led to an alcohol addiction. When my wife and I learned of this, we invited him to move back home, and encouraged him to seek help, with mixed results. Over the last fifteen years, various stints in rehab have offered glimpses of hope followed by relapses.

That Friday, I drove Interstate 81’s compass-precise northeast route, 360 miles nearly nonstop, following the Roanoke Valley, James River Valley, and then Shenandoah Valley from my daughter’s home in Virginia to Locust Lake State Park in eastern Pennsylvania. The lake and camping area of the park were nestled alongside Locust Mountain in the Appalachians’ Ridge-and-Valley range, an oasis of second-growth forest and wetlands surrounded by land first mined for coal in the middle of the 19th century. These forests were harvested to build and support the mines and tanneries but have been untouched since.

By 6:30 on one of the longest days of the year, I’d found a campsite, set up my tent, and scrounged for dinner at the camp store. (One apple was all that remained from the food I’d started out with that morning in Roanoke.) I sat at a picnic table edged with moss, pieces of sunlight filtering down on a slant, illuminating the west side of gray tree trunks. Streaks of light green foliage angled toward the ground, against a backdrop of darker green shade. Sixty feet up, through a canopy of northern red oak, chestnut oak, red maple, eastern hemlock, tulip poplar – blue sky.

I was surrounded by an understory of mountain laurel in bloom, of ironwood and sassafras saplings. Good Sir Chipmunk, with his handsome stripes, wandered through my campsite to see if I had anything for him. I tasted the sassafras leaves, a childhood favorite, chewing one into a creamy mush, conjuring up memories of its earthy aromatic flavor.[2]

After finishing a long rehab in Austin four years ago, Jesse seemed to be making peace with his life, but a double charge of DUI and DWOL landed him in jail. One of the terms of his probation was that he wear an ankle monitor and report his sobriety via a breathalyzer, those items costing him at least $600 a month to rent, a heavy burden for anyone trying to get back on their feet.

In the past year, unable to keep up with the rent of an apartment he shared with a friend from rehab, Jesse was asked to move out. Since then he’s been living in his tent in various spots around Austin, relocating when the scene got too volatile. Spending a single night camping, by my choice, in Pennsylvania woods, I think of Jesse doing that night after night, by necessity, in Austin. We’ve been corresponding by email, my small attempt to be there for him, and to be with him. His dispatches are both heartening and heartbreaking:

Met a girl named Deseree. She gave me a dollar. Well, two. Followed me into the Home Depot parking lot. Shared stories about life and her cigarettes.

I told her my name. She had bad memories of Jesses and told me the stories. Reaffirmed my belief that there can be only one. As a pacifist I guess I just have to outlive them all.

Been a long time since something like that has happened. Sitting on the curb, talking, smoking her menthols. Said she had never done anything like this before.

I have, but not with you. So, I guess I haven't either.

The camping area was quiet, just two campsites within view – a young couple and another couple nearly my age. The lake was a half-mile away by trail, and I could hear the faint sounds of children laughing and squealing with delight, while nearby birds intoned vespers, the last songs of the day. I made dinner with what I’d found at the camp store: Round Top white bread, Kraft American singles, mayo. I thinly sliced the apple to add some crunch to my sandwich while sipping from a waxed carton of green tea brewed at Guers Tumbling Run Dairy, located in nearby Pottsville, home of Yuengling Brewery, which has been in business for nearly 200 years. In 1930, the brewery survived Prohibition by opening that dairy.

Dude threatened me tonight. –“You got a problem with somebody?” –“You think you can just walk by me?” Snatched at my pockets. –“What you got?”

Walked away and stole a bus ride. It ain’t safe no more. Makes me sad. Feel that there should be unity amongst the desperate despite disparity. Common bond for fuck’s sake.

Off to sleep in an alley behind a church. Help them in the morning. I like helping. And because 7 bucks is 7 bucks.

I welcomed sleep, although in the middle of the night, I awoke to the sound of an animal heavily treading on dead leaves outside my tent. As the first rays of sunlight peeked over the mountain, I studied a wood thrush’s flutelike two-part call moving from tree to tree through the woods. Packing up my tent, I discovered, beneath the dead leaves, moss completely covering the ground.

Surrounded by native prairie which is sort of sanctioned to not be fucked with. ’Cept they mow it. Which seems not right.

Still full of native flowers. I wear them in my hair. Not that I need adornment, but shit, I will wear my environment like a boss.

Out of the campground and down the mountainside past religiously segregated graveyards – this one for German Lutherans, that one for Byzantine Catholics – and into Mahanoy City, a five-by-twenty-block coal mining town squeezed into a narrow flat stretch along a creek. Before getting back on the road, east toward Long Island, I stopped at the 123 Cafe for breakfast. After requesting flapjacks and coffee, I overhear three women at a nearby table all order scrapple with their eggs, and realize I missed a chance to try that local specialty.

I woke up this morning thinking of you. That I should tell you what is going on and how I am doing. I’m back to work through a temp agency. That’s sort of adjacent to what I wanted to tell you.

Life out here is strange; I need to get out. I know that I got myself where I am and am the only one that can change that. I am surrounded by people who blame others for their situation and expect someone else to get them out of it. That mentality doesn’t work. So they just get angry. It’s a hard environment to live in.

Although homelessness has reached crisis status, there have been successes addressing it. In the last ten years, Houston, Texas, has reduced its homeless population by 63 percent, thanks to its “housing first” program, which has moved over 250,000 people straight from the streets into apartments, not into shelters, not with the prerequisite that they’ve been weaned of drugs, or completed a 12-step program, or landed a job, or found God.

I try to find magical shit in life to keep me moving. There are good people and I try to help them. The sky last night at dusk: clouds torn to shreds and ribbons, layered, glowing pink and orange. It was beautiful. I told the other people on the bus to look out the window at it. None of them looked up from their phones. I saw it and I hold it with me because ... fuck, it was beautiful. I can’t help the people who don’t want to see something so magical.

Couldn’t sleep that night because there were gunshots and a lot of strangers around. Apparently some cop was involved and is now suspended. Meth, ice, clear, whatever you want to call it is an epidemic here. I don’t even know what it is now; it’s like a mystery drug that everyone is on because it’s dirt cheap.

It’s hard to stay positive surrounded by so much negativity and complacency. I guess that’s what the clouds are for. I never forget that there is so much that is wonderful in this world. I have so much to say and no one really to say it to, so I’m trying to write it down.

Be well, Papa

The documentary Lead Me Home ends with Angel Olsen’s song “Endless Road”: “Well, every road I see/ Leads away from me/ There’s not a single one/ That leads me home.” Still, I hold out hope for Jesse, and for all homeless people, that they may find a way home.

Footnotes:

[1] The 2021 film by Pedro Kos and Jon Shenk was an Oscar nominee in the documentary short category. It’s available for streaming on Netflix.

[2] Dried and ground sassafras leaves are the main component of filé, used as a spice and thickener in Louisiana Creole cooking.

4 May1970 / 30 May 2022: On Gun Violence

Minutes after the Ohio National Guard opened fire on protestors at Kent State, Mary Ann Vecchio kneels over the body of Jeffrey Miller.

Every year on May 4th, I stop for a few moments and go back to 1970. I was fifteen years old, living in Stow, Ohio, six miles from the Kent State University campus, when four students were killed and nine others wounded by National Guard troops during an antiwar demonstration. When I taught at Cedar Rapids Washington High School, the song I’d choose to play between classes on that date would be Neil Young’s “Ohio,” and sometimes the song would provide access to a teachable moment.

I came of age during the Vietnam War. It was one of the issues my father and I would butt heads over at dinner, to the discomfort or boredom of everyone else at the table, from my mother down to the youngest of my nine siblings. However, through these clashes with my father over the war and the protests against it, I not only sharpened my argumentative skills but also began to define my personal ethics.

I took the not unusual position that the war was wrong. No one had been able to persuade me that the United States should be militarily involved in a civil war taking place in a small Southeast Asian country. The domino theory seemed the concoction of paranoid minds. I didn’t know whether I could claim to be a pacifist, but when my dad took me on his annual Thanksgiving morning hunting trip after I turned fourteen, I refused to fire the .22 caliber rifle he’d handed me. When they flushed a deer from a thicket and Dad yelled, “Shoot, Dave!” I couldn’t, squeezing back tears. And the next Thanksgiving my parents decided to start a new tradition: a family hike followed by touch football.

In 1968, Nixon won the presidential election after a campaign based primarily on scare tactics, claiming he alone would be able to “lead us in these troubled, dangerous times,” pledging to “rebuild the respect for law,” and promising “we shall have order in the United States.”[1] He also vowed to scale back U.S. involvement in Vietnam, but that wasn't happening. On April 30, 1970, he announced on national television that the United States had invaded Cambodia, expanding the war. The next day, Friday, May 1, protests erupted on college campuses across the nation. At Kent State, on a large, grassy area in the middle of campus called the Commons, an antiwar rally was held at noon, featuring fiery denunciations of the war and Nixon. Another rally was called for Monday, May 4.

Between 1964 and 1973, nearly 2 million men were conscripted into military service so they could travel halfway around the world to fight a war that made little sense to them. In 1969, the Selective Service System held its first draft lottery, a random selection process. (In previous drafts, the method had been to draft the oldest men first.) Born in 1954, I wouldn’t be eligible for the draft for another three years. But I knew by heart Country Joe McDonald’s “I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-to-Die Rag,” Buffalo Springfield’s “For What It’s Worth,” Phil Ochs’ “I Ain’t Marching Anymore.” And I’d absorbed the antiwar messages of e.e. cummings’ “next to of course god america i” and Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five.

That Friday night after the rally at Kent State, anger seethed in the Water Street bars and eventually spilled out into the downtown streets, escalating into a confrontation between protestors and local police. Store windows were broken, and beer bottles were thrown at squad cars. The next day, Kent’s mayor asked Governor James Rhodes to send in the Ohio National Guard.[2] By Sunday, nearly a thousand soldiers occupied the campus, lending it the appearance of a war zone. Rhodes flew to Kent and, at a press conference, scolded the protesters, promising to apply the full weight of the law in dealing with them.

As was true of everyone, the war had touched me. I had a cousin who died in Vietnam on April 5, 1966, at the age of 19. The previous five summers, his family and two others would join us for a week, jam-packed into two rental houses a block from Lake Erie beaches. My next-door neighbor Jimmy Flowers went to Vietnam and returned radically altered – as Jimi, wearing a scruffy beard, shoulder-length hair, and a thousand-yard stare.

Although Kent State officials had informed students that the May 4th rally was prohibited, a crowd began to gather, and by noon, the Commons was filled with 3,000 people. About 500 core demonstrators were gathered around the Victory Bell at one end of the Commons, another 1,000 students were supporting the active demonstrators, and an additional 1,500 students were spectators standing around the perimeter of the area. Across the expanse of lawn stood 100 National Guard soldiers armed with M-1 rifles. The students were ordered to leave. When this had no effect, several Guards hopped in a jeep, drove across the Commons to tell the protestors to disperse, but quickly retreated when their command was met with angry shouting.

I was a student at Walsh Jesuit High School in Cuyahoga Falls. The Vietnam War came up often as a topic of discussion, especially in our Theology classes. One of the leading antiwar activists and pacifists at that time, Daniel Berrigan, was a Jesuit, and the majority of the Jesuits at Walsh supported his efforts. Brother McDonough, my 20th Century American History teacher, would later persuade me to canvass for the 1972 presidential campaign of George McGovern, the liberal Democratic senator from South Dakota. The 26th Amendment of 1971 had corrected a gross injustice by granting eighteen-year-olds (being drafted to fight in Vietnam) the right to vote, but my first vote didn’t alter Nixon’s landslide victory.

The National Guard troops locked and loaded their weapons, fired tear gas canisters into the crowd around the Victory Bell, and began to march across the Commons to break up the rally. The protestors retreated but then counterattacked with yelling and rock throwing. The Guard began retracing their steps until they reached what was known as Blanket Hill. As they arrived at the top of the hill, 28 of the more than 70 Guardsmen suddenly turned and discharged their weapons. Many shot into the air or the ground. However, some shot directly into the crowd. Altogether 67 bullets were fired in a 13-second flurry.

The victims were all a football field or more away from the National Guard when they were hit. Jeffrey Miller and Allison Krause were active demonstrators. William Schroeder and Sandra Scheuer were killed as they walked to classes; Schroeder was shot in the back. A photograph of Mary Ann Vecchio, a fourteen-year-old runaway screaming over the body of Miller, appeared on the front pages of newspapers and magazines throughout the country.

A number of our classmates lived in Kent, and news of the shootings quickly spread through the school hallways. We spent much of the rest of that week, first, in informal discussions about the event. Then the dam burst and the discussions spilled over into a range of topics, including education in general and our school in particular. One session got especially heated. As we expressed our grievances and declared we should be educating ourselves, Father Anderson slowly nodded, smiled, and said, “That’s exactly what you’re doing.”

The Walsh Jesuit High School Pioneer newspaper staff in 1970. I’m the curiously proud one in the left middle of the group.

Three hours after the shootings, the university was closed, not to reopen for six weeks. I was a cub reporter for the Pioneer, “published by and for the students of Walsh.” One of the juniors on the staff proposed we bypass the roadblocks that had been set up by taking back roads into Kent. I didn’t have a driver’s license but offered to ride along with him. I’m not sure if we were merely curious for our own sake or hoping to get a news scoop. In either case, that curiosity would not be satisfied. The campus was deathly still, 21,000 students suddenly gone, leaving no evidence of Monday’s tragedy.[3] Every non-essential downtown business was shuttered. Stoddard’s Custard, the Kent Road drive-in where my Little League baseball team went for soft-serve treats after every game, win or lose, was boarded up.

Looking back, I can’t help but compare that tragic event[4] to the world we live in today. Was it a forewarning that the double-barreled pressure of fear and hatred in an environment of widespread gun ownership would inevitably result in gun violence? Our frequently irrational and always inflated fears about personal safety have fed a gun epidemic. There are now more guns than people in the United States, and gun owners firmly believe this fact makes them safer. The students and teachers at Ross Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, didn’t feel safer. Nor did the shoppers at Tops Friendly Market in Buffalo, New York. Nor did the 17,798 Americans who have died of gun violence this year, as of Memorial Day.[5]

Gun violence is a multifaceted problem, and gun control isn’t the sole solution, but most Americans agree that universal background checks would be a positive step, and many agree that semi-automatic assault-style guns should be banned.[6] Lawmakers need to stop listening to the gun industry and NRA and start listening to the people. Upon watching the breaking news footage of the Kent State massacre on TV, Neil Young walked off into the woods and wrote “Ohio.” The haunting outro refrain memorializes the “four dead in Ohio.” To commemorate the thousands of victims of mass shootings in the U.S. since then, the song would have to go on for a long time.

Footnotes:

[1] These quotes from his televised campaign ads pandered to voters shell-shocked by recent events such as the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Bobbie Kennedy, the race riots and antiwar protests in U.S. cities, and the demonstrations at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago.

[2] Reluctance to serve in Vietnam had led many young men to join the National Guard, aware that they would not likely be sent to Vietnam.

[3] We didn’t see the bullet embedded in Solar Totem Number 1, a steel sculpture on the Commons. At the request of the artist, Don Drumm, the bullet is still there, a quiet memorial.

[4] This would not be the only mass shooting on a college campus that month. Eleven days later, city police and state patrol officers opened fire on Jackson State University students, killing two and wounding twelve.

[5] Per Gun Violence Archive data.

[6] Per The Pew Research Center’s Key Facts about Americans and Guns.

On the Road in 1980, Part the Last

Caye Caulker, Belize, in the late 1980s

Wednesday, 16 April. Before catching a small skiff from the Belize City docks to Caye Caulker, I exchanged travelers cheques for Belizean dollars[1] and bought some fruit. A one-hour trip skipping across Caribbean waves brought us to a coral island twelve miles off the coast, five miles long, north to south, and one mile wide. The island was situated just east of the 190-mile Belize Barrier Reef, the second longest coral reef system in the world.[2] That first day, I fell in love: the water was mildly choppy at best, pristinely clear, just cool enough for comfort, and teeming with tropical fish. I walked in up to my waist and dove, swimming underwater, kicking my legs like a frog, gobsmacked by the rainbow of small fish flitting around me.

Caye Caulker was a laid-back paradise, explaining the number of young North American and European travelers who had washed up on its shores, drawn by word of mouth. On the island’s windward side, the fairly steady trade winds kept the mosquitoes and sand fleas at bay. I settled into the idea of becoming a beach bum – whiling away my days doing a little swimming and snorkeling … a little sailing and fishing … cooking meals, playing music, getting high with friends … kicking back and letting go.

By Friday, I was hatching a plan with Bruce, Cheryl, and Ruth to rent a house on the island. I’d caught a truck ride and then skiff ride from Punta Gorda to Caye Caulker with Bruce, and I’d crossed paths with Canadians Cheryl and Ruth in Livingstón and Punta Gorda. We scouted around and soon located a house on the southern tip of the island renting for $25BZ a week. It had the basics – stove, refrigerator, indoor plumbing, beds. We bought a supply of vegetables and fish from the local co-op, where freshly caught red snapper and jack crevalle sold for $1BZ a pound, and started cooking. The house was located in a coconut palm grove, so we were using coconut milk and/or meat in all our dishes. And I’d begun constructing a percussion drum from coconut shell halves. The four of us got along well based on our shared appreciation of coffee, music, and marijuana.

We were living on island time. My Rastafarian friend Charlie just happened to sail up from Punta Gorda and settle in nearby. The notes of his wooden flute came floating from his camp on the beach. At the hostel where I stayed the first two nights, I’d found a copy of John Irving’s The World According to Garp. The opening fifty pages had been ripped out, likely used to help start some traveler’s campfire, but I was enjoying rereading the last 550 pages. Common yellowthroats, little warblers known as yellow bandits, hung out by our back doorway, eating flies and sand fleas, flitting about, even hopping into the house.

On Monday, I made coconut bread – using the milk, meat, and oil of the coconut[3] – and added the finishing touches to a chowder Cheryl had started with fish caught by Charlie and his friend Freddie. On Tuesday morning, I made another loaf of the bread at the request of my housemates, and cooked up a breakfast slumgullion for six, frying an onion, adding apropos leftovers from the fridge, and scrambling in eggs. I was completely out of B-dollars, but others supplied the food and I did the cooking, taking pleasure in serving as cook and housekeeper for our improvised family.

It would rain most nights and then clear up during the day. I had gotten used to the occasional hassle of the fleas and mosquitoes; the others not so much. By midweek, Bruce, Cheryl, and Ruth had moved on. Another Canadian, Marcos, moved in with his Belizean girlfriend. Then two Swiss guys, Pascal and Alain, joined us. Charlie had settled into a nearby house, but spent most of his time at our place, sometimes good energy, sometimes exhausting. He had found a way to hustle every pretty girl on the island.

On Thursday, after breakfast, a couple of us got high and walked into town, went for a swim, and were soaking up sun and coconut oil on one of the piers when we learned that Paulo and George, two local fishermen, were taking folks out on their sloop. We joined the group, sailing out to a spot on the lee side of the reef and dropping anchor. Masks and flippers were available, so I dove to get a close look at the amazing variety of colorful fish darting among the coral. After an hour, we got back on the boat and sailed into deeper waters near the southern end of the reef. When Paulo and George went diving for conch, many followed to watch, but I headed a different direction toward the reef. As I was admiring a beautiful school of yellow-finned goatfish and fluorescent blue triggerfish, I happened to notice a shark, about five-foot long, slowly patrolling the waters three meters below me. A bit spooked, I swam directly back to the boat. When I later mentioned my sighting to Paulo, he laughed, “Ah, Caribbean reef shark – you kids always find the sharks.”[4]

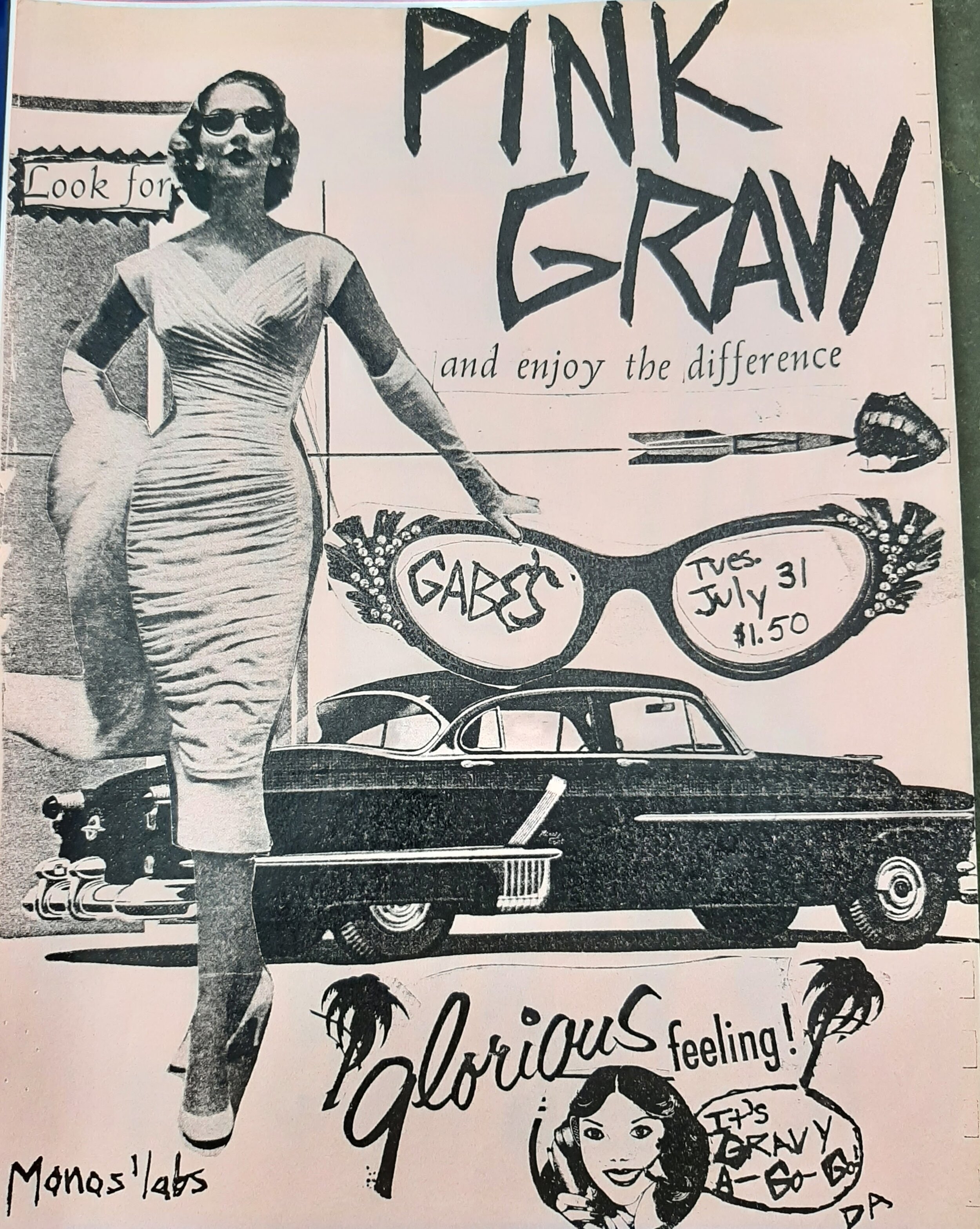

As the expiration date of my Belize travel visa loomed, I faced the realization that this three-month trip had run its course. I began to think about my return to Iowa City and what I would do when I got there: Help wrap up the issue of Police Beat, the lit mag I was co-editing. Start a bagel street vendor business. Take classes at the university – Spanish, French, film, poetry workshop. Reconnect with the crazy music-making of my Pink Gravy friends. And reconnect with Pat and little Sierra, see if there was still a place for me with them. It felt like my life was waiting for me to rejoin it.

Syd’s Restaurant & Bar on Caye Caulker

My last night in Caye Caulker, I made a hearty rice-veggies-cheese casserole for our household, then strolled down to Syd’s Bar to raise one last glass of stout and bid goodbye to my friends, especially Freddie, who’d become a good pal and who still owes me 5 B-dollars. Next morning, I caught the Mermaid, the seven o’clock boat to Belize City. As we approached the harbor, I asked the skipper for directions to the airport. He took it upon himself to call Kimba International Airport, found a TACA[5] flight leaving for Miami at 10:40, and called a taxi for me. I sailed through the morning traffic to the airport, bought a ticket, passed through immigration and customs, all in a blur. My first plane ride, I was enthralled by the dance of the flight attendants demonstrating how to use the life vests and oxygen masks. We soared over the blue Caribbean and its pattern of reefs and islands, then the green Everglades, then Miami International Airport.

Back in the US of A, I walked out of the airport, got my bearings, and began hitching north, excited to be back but also disturbed by the jarring reminder of this country’s superfluous affluence. I thought back on how the trip had begun, my commitment to “the interior voyage … to trace that path.” I had promised to pursue this inquiry: “Are the things I do and say equivalent to my feelings, my emotions, my convictions?” I couldn’t say I had returned a changed person, but I had come to know myself a little better.

When I now reflect on this trip, The Barr Brothers’ song “Defibrillation” and these lines come to mind: “Where would you wander? / What would it mean? / There might be saviors, but no guarantees / … It’s not my nature to pretend / That any one road leads to any one end.”

Footnotes:

[1] At an exchange rate of $2BZ for $1US.

[2] To preserve the biological diversity of this coral reef, UNESCO designated it a World Heritage Site in 1996. Although Belize has taken notable steps to protect it from bottom trawling and offshore oil drilling, the reef is still threatened by oceanic pollution and global warming.

[3] To process coconut oil, shred coconut meat, soak it in water, strain the milk from the meat, and cook the milk at a low simmer until the oil separates and rises to the surface.

[4] Stephen Spielberg’s Jaws, released five years earlier, had left all us kids with an unfounded fear of sharks.

[5] Transportes Aereos del Continente Americano, a Salvadoran airline now known as Avianca.

On the Road in 1980, Part 8

El Cerrito del Carmen, site of a hermitage on the northern edge of sprawling Guatemala City.

“How much larger your life would be if your self could become smaller in it; if you could really look at other [people] with common curiosity and pleasure…. You would break out of this tiny and tawdry theatre in which your own little plot is always being played, and you would find yourself under a freer sky, in a street full of splendid strangers.” –G. K. Chesterton

Martes, 8 de abril.[1] The package of literary magazine submissions finally arrived that afternoon. I was staying in Guatemala City at Pensión Luna, impatient to move on. I bided my time by wandering the crowded, rackety streets, hiking to Parque Minerva, on the northern edge of the city, where I shot baskets with a kid at a beat-up hoop and watched a local semi-pro baseball team practice. Atop a nearby hill, I came upon the quiet gardens of a beautiful old church, La Ermita del Carmen.[2] Following the cloister’s winding path, I thought about the next stage of my journey: down from the Highlands, northeast to Puerto Barrios and the Caribbean coast.

I started that 300-kilometer trip the next morning, walking far enough to get out of the city and quickly hitching a ride from two friendly foresters driving a flatbed truck, who took me almost halfway, to the town of Santiago. The day warmed up as we drove down into the lowlands and along the Río Motagua. I soon caught another ride from two guys transporting a truckload of sandias. I gently clambered atop the pile of melons and settled in for the ride, the last sixty kilometers growing tropical lush, the road lined with orchards of mouth-watering sapotes, papayas, guayabas, mangos, tamarindos.

Arriving in Puerto Barrios at four PM, I located a pensión and then went down to the docks to suss out information for the ferry to Belize. The ferry crossing Bahia Amatique to Punta Gorda would depart at dawn the next morning. I had enough quetzales for the ferry ride but not for the Oficina de Migración’s exit fee. Rather than waiting for the next Punta Gorda ferry, I decided to take the first ferry after the banks opened, which would take me across a smaller segment of the bay and the wide mouth of the Río Dulce to Lívingston, still in Guatemala.

While I was at the docks, I watched a departing ferry and two Aussies missing the boat by seconds. I got to talking with them, horticulturalists from Canberra collecting tropical plant seeds for their farm back home. We all had an evening to spend in Puerto Barrios, so we smoked some of their hash and drove around in their rented car, winding up at a whorehouse, where we drank too many beers and engaged in friendly banter with the Belizean sex workers. Port towns are always lively and captivating, but I was hoping Lívingston would be more laid-back.

On the ferry ride the next day, I met Liz, a charming Brit from Salisbury. We got off the ferry at the dock, both of us looking for a place to stay, and were led by a young kid to a pensión that offered a single room with two beds. We just looked at each other a minute and said, “Why not?” After unpacking, we headed out to explore the town, almost immediately running into two American girls I’d met in Antigua. I had to extricate myself from an awkward moment, since they knew me as David and I’d just introduced myself to Liz as Francisco. All good though.

The next day we rented a cayuco[3] and paddled across the wide mouth of the Rio Dulce to an isolated beach. Although the water was choppy and the cayuco tippy, we crossed without incident, enjoying each other’s company as we shared tales of our journeys and a picnic of sandia and aguardiente.[4] Liz was a social worker in Edinburgh, a gentle heart, with the wisdom and sensibility of an experienced traveler. When we returned late in the afternoon, the wind had picked up, as had the waves. The cayuco capsized twice, but after a few false starts and a lot of bailing, we learned how to balance the counteracting forces of river current and sea winds to keep the craft upright, laughing afterward about our little fiasco.

I was smitten by Liz – tall, lithe, athletic, adventurous. In my mind, she fit the mold of intrepid British explorer-travelers such as Gertrude Bell and Beryl Markham. Our last night together, I finally proposed joining her in bed. A bit shy about such things, never wanting to assume, I’ve always had a hard time distinguishing between the signals for friend and lover. Liz laughed, “I’ve been wondering when you’d ask.” We spent a sweet night together before she headed toward Antigua and I caught the ferry to Punta Gorda.

The quiet Punta Gorda waterfront. The craft in the foreground is a cayuco.

Formerly known as British Honduras, Belize had been a British Crown Colony for over a century. The name change had occurred in 1973, but the country wouldn’t gain its independence until 1981. Punta Gorda, the southernmost coastal town of Belize, was a small fishing port. I found a place to stay at Madman’s 5 Star. Trust me, the five stars of the name were aspirational at best, but Madman offered a cozy restaurant – a single long table with benches on his enclosed front porch – serving wholesome food in robust portions, and behind his house a palapa,[5] where I hung my sleeping hammock.

I had finally found the seclusion I needed to read and comment on the eighty submissions to the literary magazine I was co-editing with Michael Cummings, which we had decided to call Police Beat.[6] When Mrs. Madman heard about my project, she loaned me a spare table that I repaired and set up as my desk. After three days of editorial work, I sent off the letter that included my notes on which pieces should be included in the issue.

The first and only issue of Police Beat. The postcard on the cover had arrived mysteriously at my address two years prior.

My first afternoon in Punta Gorda, I befriended a gregarious dreadlocked Rastafarian named Charlie, who had spent time in Canada, the U.S., and the military, but who now tended a field of ganja somewhere in the backcountry and lived on his sailboat. We met two Canadian girls whom Charlie invited to go sailing with us, but I wasn’t much of a first mate, and we never got out of the inlet he’d been anchored in. Instead, we hung out on the boat and got high while Charlie played his guitar. On shore later, as we walked through town, Charlie accosted a young British soldier, all the enmity toward the colonial oppressors seeming, at least to me, to explode out of nowhere.

On Saturday night, I gave in to Charlie’s nagging and let him introduce me to a food vendor on a dark side street who dished up “ground food” – yams, potatoes, plantains, all cooked with pigtail and lots of grease, served on wax paper and eaten with our fingers. The bars in Punta Gorda sold good stout in plain brown bottles. Everyone cooked with coconut oil and milk. Sweet coconut bread buns were sold by little girls who walked the grassy lanes of Punta Gorda, carrying baskets covered with tea towels, almost too shy to show me what they were selling.

Punta Gorda was a trip. The beaches weren’t great, but I still went swimming among the jellyfish. Walking back, I chatted with some young guys gathered under a large spreading ceiba that they called “the learning tree,” and later went with a Rasta named Soul to a shanty on the outskirts of town to buy a spliff and get high right there on a Gospel Sunday afternoon. Folks spoke English to me, but when they conversed with each other, I heard an incomprehensible blend of English, Belizean Creole, and Spanish. Besides fishing, not much work was available. When people needed something, they were so laid back they’d just ask for it. Thanks to this custom, I was able to present a pair of pants I wasn’t wearing to an old man. The town was inhabited by a mix of Creoles, Garifuna, Maya, and peachfuzz-cheeked British soldiers.[7] The music was good – lots of reggae, and the funkiest U.S. music.

Madman had his finger on the little pulse of Punta Gorda. When he heard a truck transporting empty bottles would be stopping in town on its way to Belize City, he let me know I could catch a ride with it. Just one road meanders the 270 kilometers north to Belize City, and I’d heard that the hitching could be painfully slow, so I decided to take him up on the offer. It turned out I wasn’t alone.

That night, two other Americans – Bruce and David – joined me on the “empties express,” which stopped for the night in Big Falls. After sharing canned mackerel and crackers for dinner, we crawled into our hammocks, rising at four AM to be on our way. From the back of the truck, we got a good look at the dense tropical forest we were passing through. Most houses were mounted on stilts; churches adhered to the English Colonial style. We helped load the crates of empties as we stopped in shantytowns – Hellgate, Bella Vista, Georgetown, Santa Cruz, Silk Grass, Bocotora, Hattieville. By noon, we were being dropped off at the Belize City docks, where the three of us found a skiff going to Caye Caulker, 30 kilometers northeast into the Caribbean.

Footnotes:

[1] Tuesday, April 8th.

[2] The Hermitage of Our Lady of Mount Carmel, the patroness of the Carmelites, one of the first religious orders of Christian hermits.

[3] A shallow dugout canoe carved from the trunk of a palm tree.

[4] Literal translation, fiery or burning water, made from fermented sugar cane mash.

[5] An open-sided dwelling with a palm thatch roof.

[6] After an unintentionally funny column in the University of Iowa’s student newspaper, The Daily Iowan.

[7] The Creoles are descendants of enslaved Africans; the Garifuna are descendants of Maroons (Africans escaped from slavery) who mixed with Native Arawak and Carib people.

On the Road in 1980, Part 7

One of the many alfombras (sawdust carpets) created for Antigua’s Semana Santa processions.

Miércoles, 2 de abril.[1] The first half of Semana Santa in Antigua was relatively quiet, giving me a chance to get to know the city. I attended the velaciones, or vigils, held at Iglesia San Francisco El Grande on Tuesday evening and Iglesia Escuela de Cristo on Wednesday evening. Large alfombras had been laid out before the altars of those churches by hermandades.[2] These “carpets” were intricately designed using sawdust dyed in a rainbow of bright colors, and then surrounded by a cornucopia of offerings: fruit, vegetables, flowers, candles, specially shaped loaves of bread. People came to pray, admire the alfombras, and then partake in the festivities outside on the church’s plaza. It became a bit too much – a mí me gusta la tranquilidad.[3] But I did get to taste a delicious Guatemaltecan pastry called mollete, a kind of custard-filled French toast.

Although I’d come to Antigua to witness the spectacle of Semana Santa, I grew to appreciate more the effect those ceremonies had on the people. On Wednesday night, I watched (not for the first time) the movie Brother Sun, Sister Moon and was moved by the story of Saint Francis of Assisi. I was drawn to the perfect simplicity of his life – working with his hands and renouncing all material attachments, living like the lilies of the field and becoming “an instrument of peace.” The next day, I gave away some of my clothing to Antigueño street beggars. To be honest, I did so mainly because I’d bought other clothes and didn’t want the extra weight, but the giving still felt good.

I awoke early on the morning of Holy Thursday. The kitchen of my landlady, Doña Marina, was a beehive of activity. Her two daughters, and a playful swarm of grandkids, had arrived to help prepare her annual contribution to the festivities: 600 empanadas de flan. I joined in the work: patting out dough into flat round disks, adding a dollop of flan, folding the disk in half, and crimping the edges with a fork. After we were done and while the empanadas were frying, Doña Marina invited me to join them for breakfast.

On Good Friday, the week’s activities came to a somber climax. At dawn, men on horseback, dressed as Roman soldiers, rode through the streets while beating on drums. It was a sunny morning, so I walked to the top of Cerro de la Cruz to step away from the hubbub and get a bird’s-eye view of the city and, beyond that, Volcán de Agua. Many Antigueños had been up all night working on the alfombras – most made of colored sawdust, some of pine needles and flower blossoms – that stretched through the main streets of the city. I ran into my Québecoise friend Michelle from San Cristóbal de las Casas, and we strolled around, discussing and admiring the artistry of the alfombras.

The death sentence of Jesus Christ was proclaimed at Iglesia de la Merced. And at noon, a reenactment of the crucifixion took place at Escuela de Cristo. After that, the procession began, and the men shouldering the andas trampled underfoot the beautifully crafted alfombras. Parque Central was packed with people, vendedores everywhere selling food, drinks, craft items. A shoeshine man, maybe five feet tall, got some business from the guy sitting beside me on a park bench: un lustre por 25 centavos.

Kaqchikel Maya weavers of San Antonio Aguas Calientes, using backstrap looms.

On Saturday, restless, searching for something, like young Francis of Assisi, I took a bus out of Antigua to nearby San Antonio Aguas Calientes, famous for the bright intricate textiles woven by Kaqchikel Maya women on their backstrap looms. It felt good to escape the crowds. I walked dirt roads to San Miguel Duenas, six kilometers to the south, and then another six kilometers farther to Alotenango, where I stopped at a Franciscan monastery to watch friars bless the water the farmers would need to irrigate their fields.

I climbed a steep hill past fields of corn and beans and lush café fincas.[4] As I did so, I composed a little song – “Café, café / Café, café / En las montañas de Guatemala / Hay mucho café, mucho café” – my voice ringing across the valley. To the east loomed Volcán de Agua; to the west, thin trails of smoke drifted from the twin volcanoes of Fuego[5] and Acatenango. Later, back in Antigua, the skies still perfectly clear, I could see all three, blue and formidable in the twilight.

* * *

Reflecting on the events of that week, I can’t help but think about what else was then happening in Guatemala. In San Pedro La Laguna, we talked about the dangers of traveling in certain parts of the country. The standard piece of advice was to avoid the Petén Basin, the northernmost region and home to a wealth of Maya ruins, including the pyramids at Tikal. A rumor was circulating that some young gringo travelers had disappeared in that area, but it was never confirmed.

What can be confirmed is that 1980 was the beginning of some of the most brutal years of that country’s long civil war. The Guatemalan army, with the help of right-wing death squads, had begun to implement Operation Sofia, whose goal was to wipe out the leftist insurgency led by the EGP (Ejército Guerrillero de los Pobres[6]), which sought to overthrow the repressive military government. This act of genocide is now widely known as the Silent Holocaust.[7]

The people of Antigua performed their annual reenactment of the death of a man who was crucified for leading a popular revolt against the religious and secular status quo. Rome ruled Judea, but washed its hands of the Jesus case, handing him over to the Jewish leadership. The U.S. government, having quietly shored up Guatemala’s corrupt military government for so many years, looked the other way when the latter government silenced the protests against it.

In 2018 I taught one of the most challenging and rewarding classes in my years at Cedar Rapids Washington High School, an LA 10 class that included a large number of ELL students, among which were three very quiet but hard-working Guatemaltecan immigrants. As I got to know them, I learned they were all from Santa María Nebaj, a small town in the El Quiché department, deep in the Highlands east of Huehuetenango. Nebaj was part of the Ixil Triangle, three Ixil-speaking Maya communities that were especially targeted by the state-sponsored terrorism of Operation Sofia.

It hurt my heart to imagine what their parents endured to survive. It hurt my heart to know that ICE was harassing those families and none of those students would finish the school year at Washington. It hurt my heart to realize how oblivious I was in 1980 to the tragedies unfolding around me.

* * *

At midnight, flutes and drums resounded across Antigua, announcing the Easter Vigil mass, but I wasn’t able to pull my Brother Body out of bed. I did get up at dawn when the bells of San Francisco sounded the news of Jesus’ resurrection. Lit up with candles and decked out in flowers, the church was filled with the uplifting joy of our voices singing Alleluia! As the sun rose, it poured through the three deep windows behind the altar, silhouetting the statues of saints gazing down on our congregation.

I climbed Cerro de la Cruz again to lay in the warm sun and begin reading the biography of Saint Francis I’d picked up at the English-language used bookstore. Monday morning I would leave Antigua for Guatemala City to pick up the literary magazine submissions. I had decided to change my name, something I occasionally did as I traveled. Me llama Francisco.

Note: My former colleague at Washington High School, Jim Burke, has led a number of student service teams on trips to Antigua during school breaks. Through the nonprofit organization ImagininGuatemala, these students have helped Guatamaltecan families build better housing for themselves while experiencing another country, culture, and language. If you'd like to support the work of this non-governmental organization, I encourage you to go to their website to make a donation.

Footnotes:

[1] Wednesday, April 2nd.

[2] Church brotherhoods or fraternities.

[3] As for me, I like the peace and quiet.

[4] Collective coffee farms.

[5] The Kaqchikel Maya call it Chi Q’aq’ (“where the fire is”).

[6] Guerrilla Army of the Poor.

[7] For more information, see Yale’s Genocide Studies Program’s report on Guatemala.

On the Road in 1980, Part 6

San Pedro La Laguna, Guatemala, on the shores of Lago de Atitlán, at the foot of Volcán San Pedro.

Domingo, 23 marzo.[1] I had made camp on a hilltop overlooking the valley through which the Pan-American Highway snaked, eighty kilometers into Guatemala. I was excited to be there, under the brilliantly green long-needled pines of the Guatemalan Highlands, an extension of the Sierra Madre de Chiapas. My first impression of the people was positive: They were friendly but self-possessed, paying only as much attention to me as was necessary. From a respectful distance I was falling in love with the Maya women, with the shy smiles on their broad faces, with the long thick braids of their black hair.

That day had started with a late-morning hike out of San Cristóbal de las Casas and then a ride from two California dudes headed for Panajachel on Lago de Atitlán. I crossed the border with them, paying two quetzales for my visa stamp and twenty for an “inspección.”[2] But the more time I spent with those guys, the more troubled I was by their bogus carelessness, their jive disdain for the land they were passing through, their mean-spirited jokes about “those little Indians in their silly costumes.” Even though I was considering Panajachel as a stop-off, I had them let me out five kilometers past Huehuetenango, the first city we happened upon.

As I prepared my dinner, I thought through an itinerary: I had a week until Palm Sunday, the beginning of Semana Santa, enough time to stay a few days somewhere on Lago de Atitlán before arriving in Antigua for its famous Holy Week celebrations and ceremonies. By then, the package of submissions for the literary magazine I was co-editing should have made its way from Iowa City to Guatemala City.

The next morning I hiked into Huehue to exchange a travelers check for quetzales and check out the market. As I wandered around, a gray-haired man approached me, asking if I wanted to buy a camisa he pulled out of his satchel: an old, tattered cotton shirt, white with blue stripes and a wide collar embroidered in a design of red and blue. I was so taken by the serendipity of the moment, and by his claim that this was his shirt, that I promptly bought it, thinking I’d try to mend it. I later learned this was a traditional shirt worn by the men of Todos Santos Cuchumatan, a Mam-speaking Maya community forty kilometers northwest of Huehue, deep in the Highlands.