My Days in a Rock ‘n’ Roll Band…

or, How I Became a Monos’lab, Part 1

When I returned to Iowa City in late August 1979 from my Cape Breton trip, I was looking for a change. I responded to a roommate-wanted ad on the New Pioneer bulletin board. This small step led me into a world of new friends and collaborators, of artists and musicians and writers, people who looked clear-eyed at the world handed down to them and engaged with that world in the guise of characters, as if it all were a play, and it was.

I met Thomascyne Buckley, a gregarious, auburn-haired art student, at her first-floor apartment in a house on Fairchild Street, and soon moved in with her and her dog Max. They’d been living there a year, and she’d put her stamp on the place. The creative chaos was both exciting and unsettling, but I soon found my footing. Hanging from trees in the backyard were boingers, musical sculptures Thomascyne had made by shaping thick aluminum wire into objects vaguely resembling tight tornado funnels. I would lie in a hammock, reading and absentmindedly strumming the boingers with anything like a drumstick to produce a shimmering and beautifully eerie sound, a coda perhaps to a particularly good poem or paragraph.

As the semester started, what we were each studying and creating led to interesting discussions across disciplines – art, literature, music. Having caught parts of a Dada Conference held at the university back in the spring, we both were drawn to the absurdist sensibilities of Marcel DuChamp, Kurt Schwitters, John Cage, and others. And we were also keeping a close eye on current issues.

In her sculpture class, Thomascyne was constructing “eggthings,” costumes made of wire frames covered in heavyweight gessoed paper, with armholes, legholes, and an eyehole, and a seam between the top and bottom that would allow a person to put it on and wear it. I was intrigued as I watched her work out the practical design issues of making wearable art. Meanwhile, she was constructing a narrative to explain these six eggthings: Dr. Bob was in the lab, messing around with some radioactive materials, when a half-dozen adjacent eggs were accidentally contaminated, mutating into these six-foot-tall eggthings.[1]

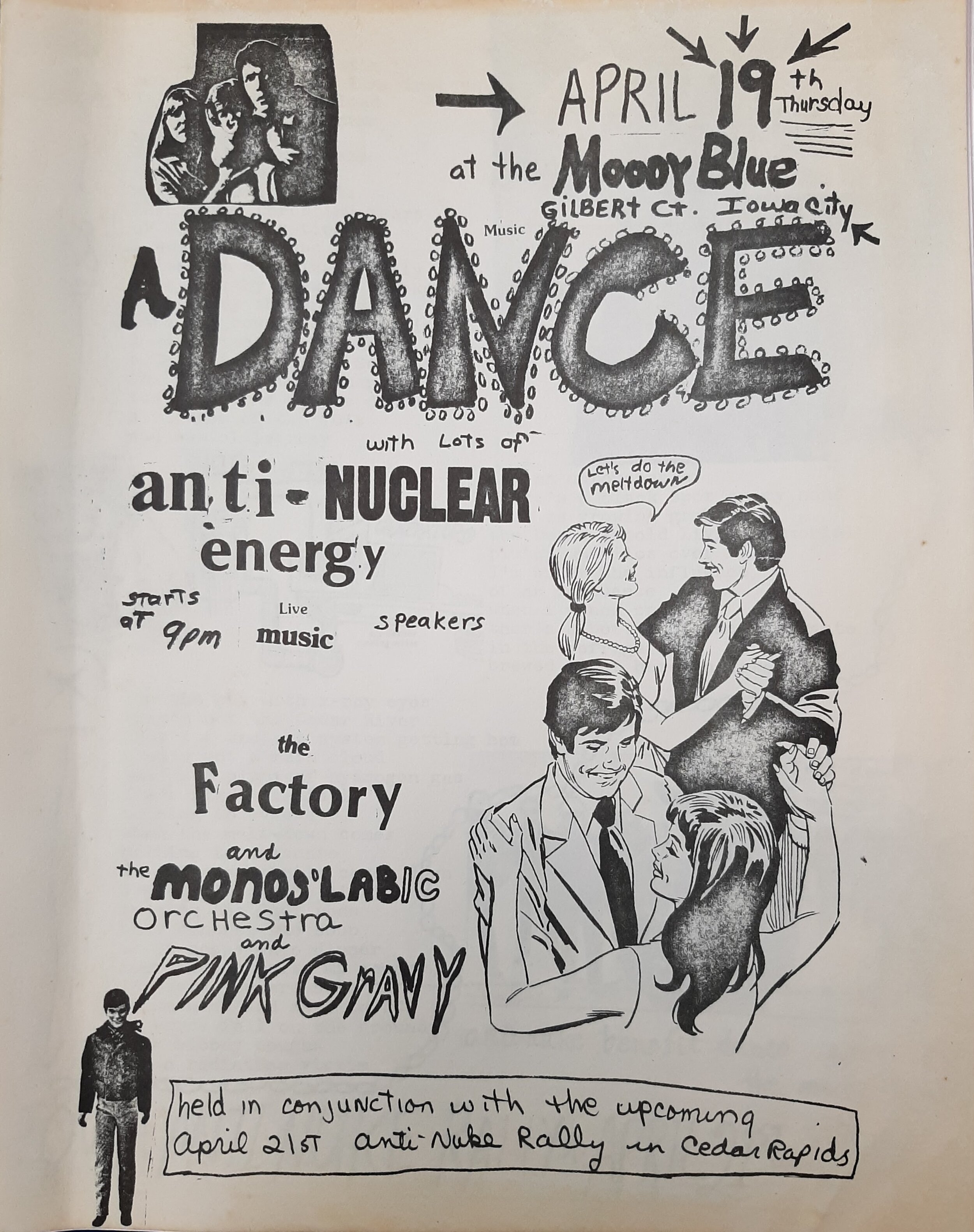

At that time, most politicians thought nuclear energy was the solution to our need for a cheap and unlimited alternative to fossil fuels. But others feared nuclear power plants were being approved and built too quickly without regard for their dangers. Those fears were realized in late March of that year when a partial meltdown and radiation leak occurred at Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania. Thomascyne’s sculptures were whimsically highlighting those dangers, critiquing them by normalizing them.

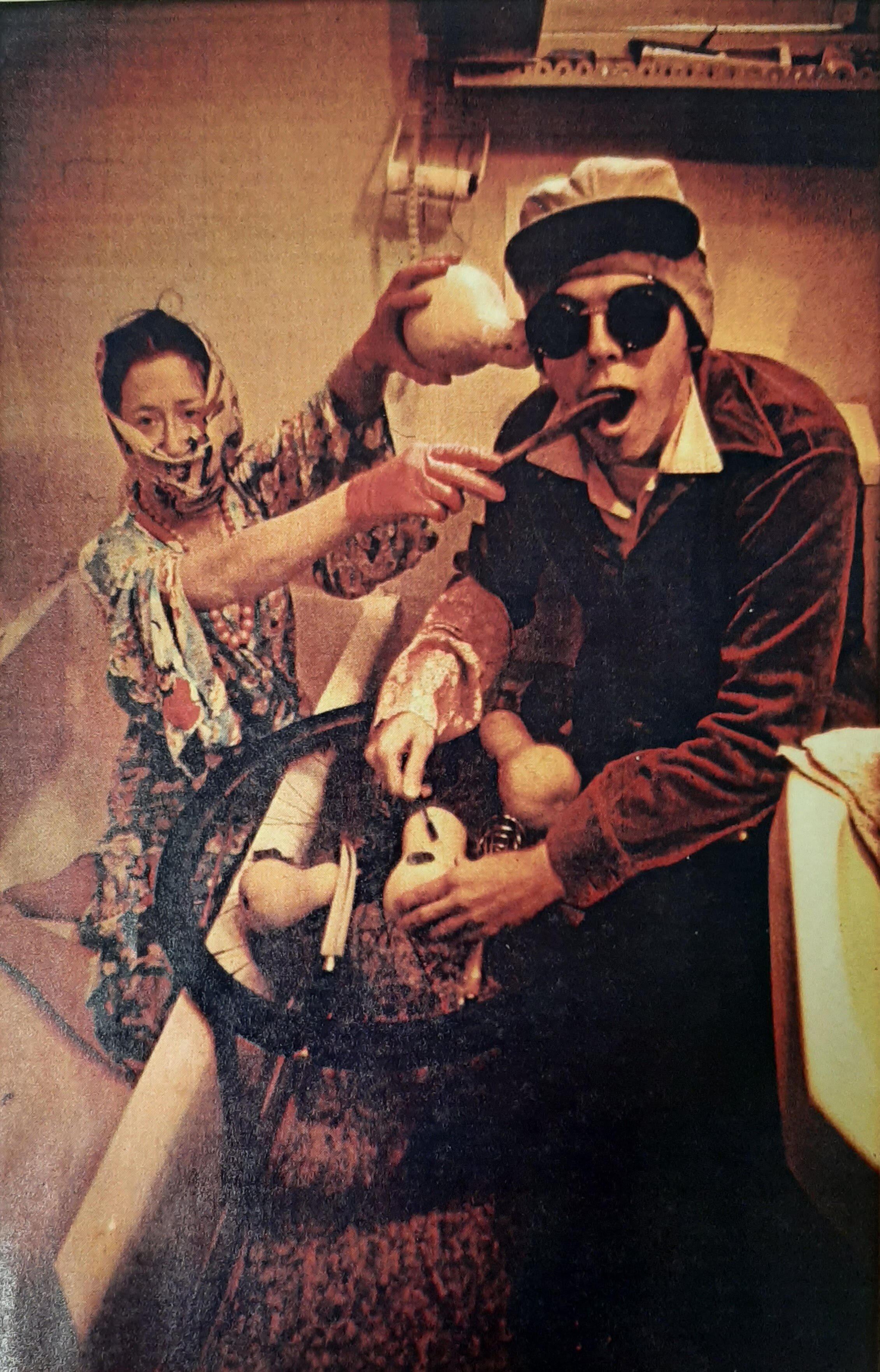

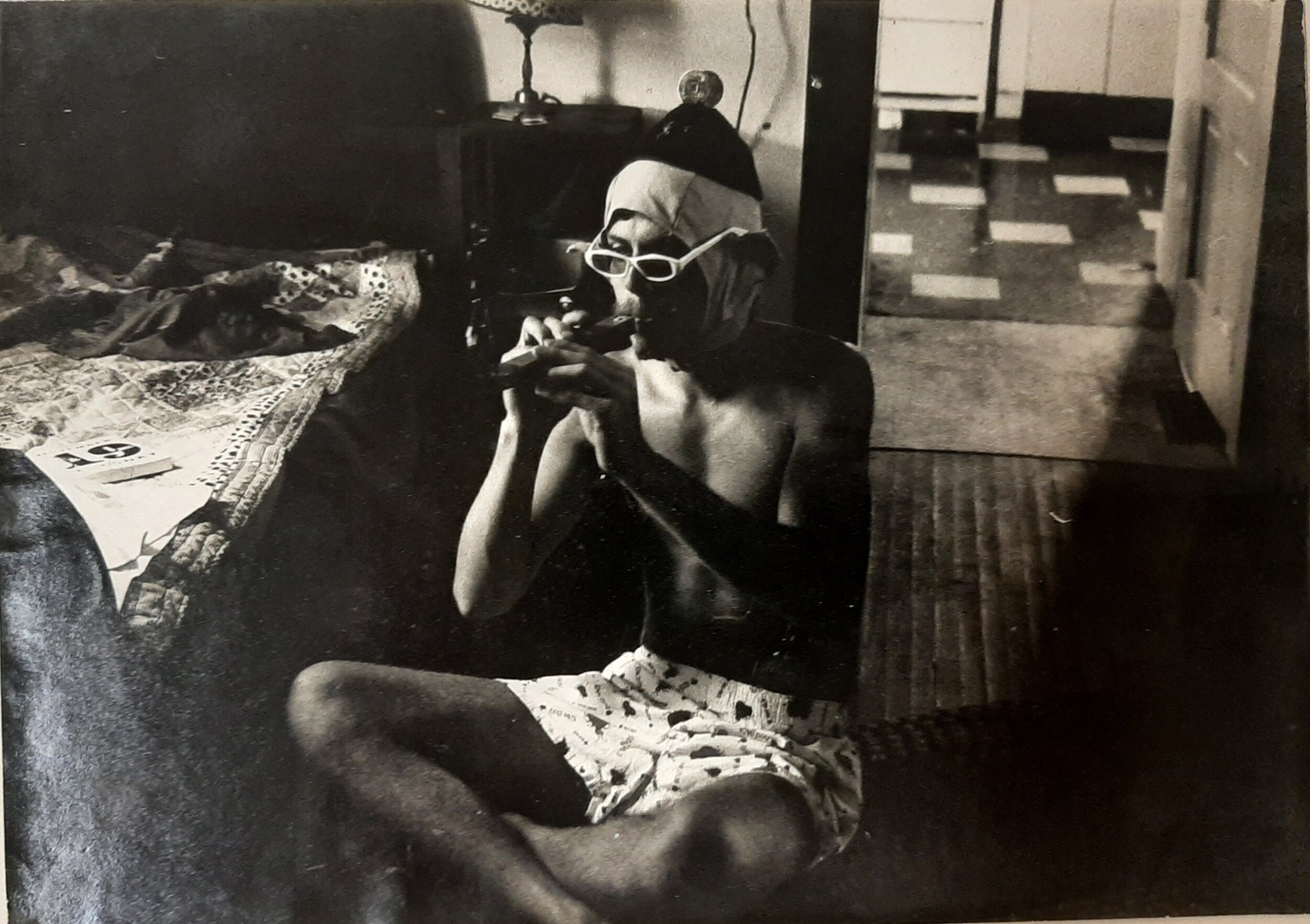

Meanwhile, one of Thomascyne’s sculpture classmates, Brenda Knox, was creating fabric head masks of characters such as Madge and Howard Nelson, Bowlo, Zippy the Pinhead.[2] These characters became model Monos’labs – clueless inarticulate suburbanites on vacation, parodies of Dick Nixon’s Silent Majority, the kind of folks who would flock to vote for Reagan the following year. Brenda and Thomascyne scoured second-hand stores, looking for outlandish outfits for the Monos’labs, the more polyester the better. Seemingly unable to fight the tide of conservatism sweeping the nation, they chose to cynically and satirically infiltrate it.

Other young artists would frequent the Fairchild Street house. Walter Sunday stopped by, lugging a large paper bag filled with combs he had scavenged from the streets. I was taken by his single-minded passion and began to do the same. These are the opening stanzas of my long poem documenting the experience:

Once upon a time, Walter, obsessed with the debris of combs,

casually left a pile of them on our kitchen table.

Black and anonymous, as common as money, they

remained there, an arrangement that lasted through the winter.

Their purpose squandered, never again would they

orchestrate the wave of hair through their fine teeth.

Then the sun returned and the snow melted, disclosing

this residue of combs scattered throughout the city.

Combs on the sidewalk, steaming with ownership,

still holding the private tangled strands of lives.

Combs made of hard rubber, DuPont nylon, all the plastic

brands—Pro, Goody, the ubiquitous black Ace, the Unbreakable …

At the suggestion of Thomascyne and Brenda’s sculpture professor,[3] all this came together as a performance of their work. Thomascyne had recruited a crew of adventurer-participants; all the eggthings were selected for their tall, lanky physiques. She had located a free piano and a pickup truck. That afternoon, we hauled the piano across town while playing it maniacally. And so it began one night in late October, near the UI Art Building, under some trees beside the river, dimly illuminated by the lampposts on the bridge.

This was the debut of the Monos’labic Orchestra. Thomascyne’s tangled tree of boingers made a musical appearance, trash cans provided a percussive element. Six eggthings – all well over six feet tall – danced and whirled and chanted: Moon, stars, planets, boing! … Omm-lette! … Je suis fou! Je suis dans la lune! A sizable crowd of students showed up, curious about what and why. It was all wonderfully messy and funny, but also at times magical and mysterious.

The eggthings were naïve and idealistic, in need of protection from a judgmental world, so we adopted them. Everyone involved in the performance realized this wasn’t over, that some kind of second act was coming. That next act took place on a slushy February day when the six eggthings returned to public life to protest the wholesale slaughter of their brothers and sisters at Hamburg Inn #2, Iowa City’s popular breakfast diner. The entire demonstration was documented – the eggthings picketing in front of Hamburg Inn,[4] a “token woman reporter” interviewing them and inviting them to make an incoherent statement of their concerns, and then a VW van suddenly appearing and a pack of RV people clambering out, chasing off the helpless eggthings, and catching up with the most hapless of them, Sonny Side-Up, across the street. A martyr to the cause, Sonny lost his life that day, his scrambled remains strewn in the alley off Linn Street

A few weeks later, Pink Gravy and the Monos’labic Orchestra performed at the Wheel Room, the bar in the basement of the UI student center. It was both a memorial concert for Sonny Side-Up and a Mardi Gras Festival celebration. Making its first appearance was Pink Gravy, the electric rock band manifestation (or mutation) of the Monos’labs. In the planning leading up this event, scraps of ideas on paper were floating around the Fairchild house kitchen table. On one of them, someone had scrawled “punk group.” Thomascyne walked in and misread it aloud: “Pink Gravy?” The name would stick.

Once again, Thomascyne served as the mastermind and agent provocateur and mother of this venture. Both Brenda and Thomascyne had great voices. Brenda played sax and flute. Thomascyne quickly picked up the electric guitar and sax. Paul added his solid lead guitar and vocals, and Chad became the quintessential quiet, steady bass guitarist. Bob was on drums, Eric on keyboards, and David Tholfsen and I on percussive energy and vocals. Alan, Scott, Kevin, and many others joined in at various times during the life of the band. I was invited to get involved because I was a poet who enjoyed disguising myself in costumes and acting goofy. I sang backup and occasionally lead vocals. I played the tubes[5] and other percussive instruments – squeak toys, boingers, bike horn, smoke alarm, as well as more traditional instruments.

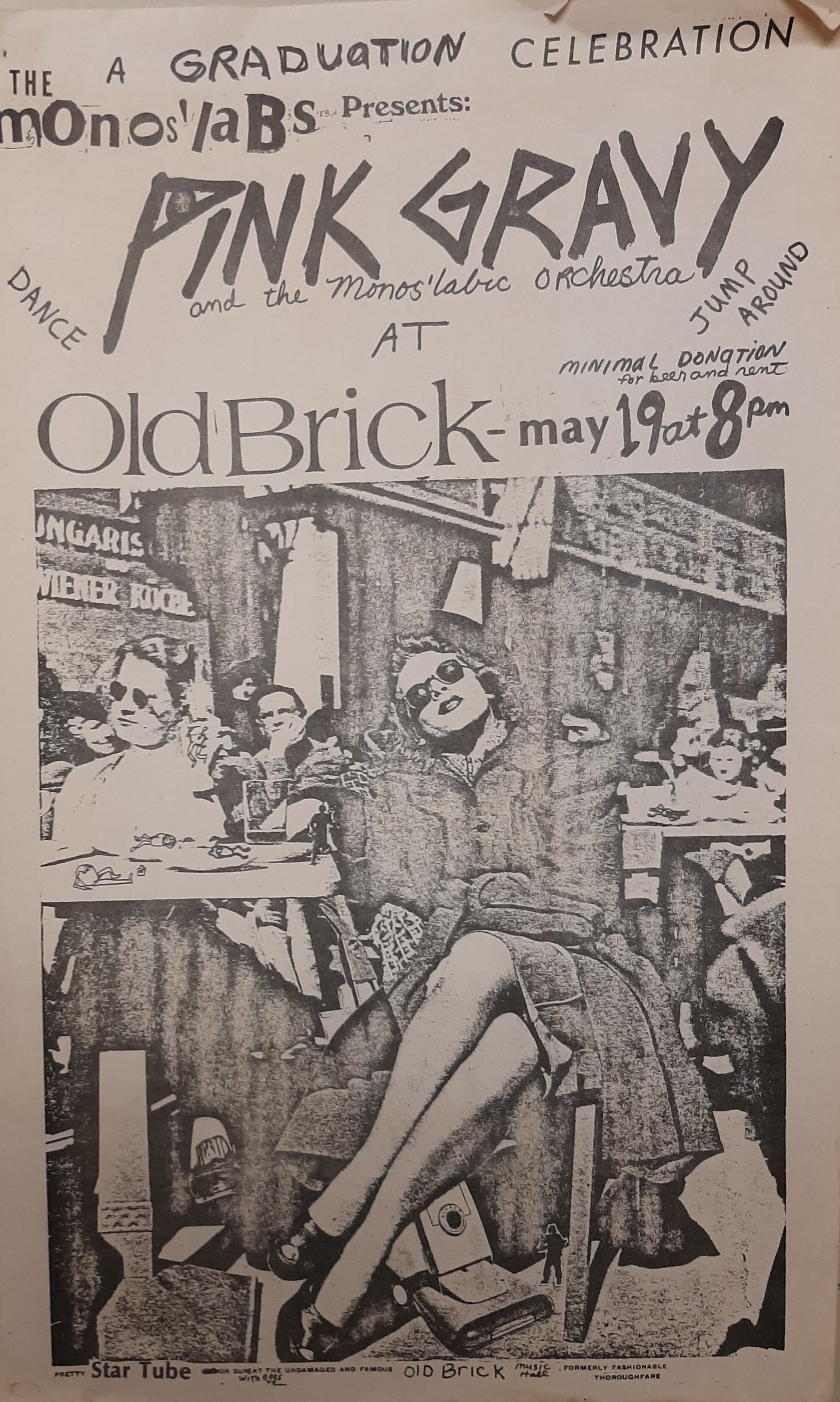

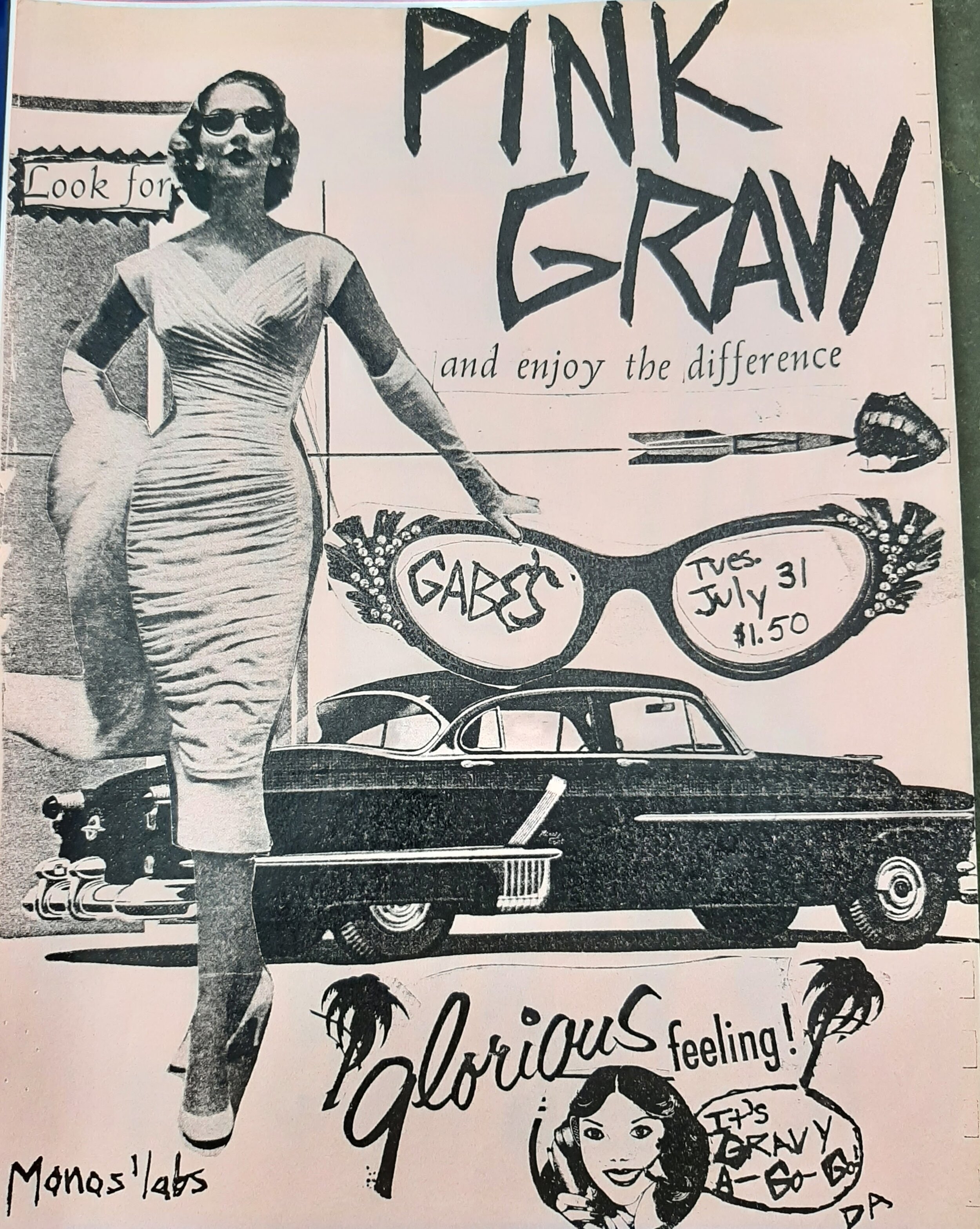

In March, we played the Wheel Room again, and in April, we were at The Moody Blue to rally support for an upcoming demonstration at the Duane Arnold nuclear power plant near Cedar Rapids, where a number of Monos’labs were arrested for trespassing. In May, we rented the Old Brick building for a Graduation Blast featuring Pink Gravy and the Monos’labic Orchestra. Brenda, who worked at Gabe’s, helped us get our foot in that door, and by July, we were playing gigs at what would become our favorite place to play. We publicized our shows by stapling bright, busy collage posters all over town (which fans would then remove because they liked the art). Much of the raw material for the posters came from magazines of the fifties, a bonus of our second-hand store scavenging. We mastered the art of xerox, sometimes making copies of copies so that the image degraded, generation by generation.

How does one explain this? We were a bunch of bored and restless kids who decided to do whatever we could to shake up the status quo, to épater les bourgeois.[6] The recipe: stir up a couple of visual artists, some writers, a few musicians, and shake vigorously, garnish with Monos’labs and eggthings. The end result was a conceptual garage band (or warehouse band since we practiced at Blooming Prairie Warehouse) that was visually interesting and musically all over the place. People came to see the spectacle, listen to our songs, and dance with us. For me, hanging with this group of people was creatively inspiring and crazy fun. As Pink Gravy would remind us in its ska number “Everybody Is a Monos’lab” – “S’labbin’s happenin’/ It certainly isn’t fattenin’/ You just gotta see it through/ Get some data from the view.”

Footnotes:

[1] According to the song “Eggtime,” by the band Pink Gravy.

[2] Madge with cat-eye sunglasses and severely coiffed hair, Howard looking vaguely academic, Bowlo a pudgy-faced Italian guy, Zippy with an actual rabbit ear TV antenna.

[3] Louise Kramer, a visiting instructor from New York City. The creation of Thomascyne’s boinger pieces had been encouraged by David Dunlap in his drawing class.

[4] One of the picket signs was a real estate yard sign that had been appropriated and mutated: “Dick IcKee real or.”

[5] Rubber shower hose, galvanized iron and PVC plumbing pipes, plastic tubing,

[6] That is, stick it to the man.