How I Came to Iowa City…

Anti-war protest on the University of Iowa Pentacrest, spilling out onto Clinton Street, May 1970

… And Found a Home

My family moved from Stow, Ohio, to Urbandale, Iowa, in 1974, while I was living in Western Kentucky. As I understood the story, my father, a liquor salesman for Seagram’s, took the fall for some company malfeasance involving the Ohio State Liquor Control Board. After he did this, the company got him out of Dodge and into Iowa, and to thank him for his loyalty, handed him a promotion – State Sales Manager. For me, the most salient point of this was I could claim Iowa residency and then pay in-state tuition at the University of Iowa.

While working on my high school senior project – an independent study of modern poetry – I had developed an interest in the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. It kept popping up in bios in the back of the anthologies I was avidly perusing, books such as The New American Poetry (1945-1960) and An Anthology of New York Poets. Even though I’d never been to Iowa and had not applied to any colleges, in my yearbook questionnaire I listed the University of Iowa as my post–high school destination. I guess that was aspirational. But when my family moved to Iowa, I realized I could make that come true.

I moved in with my family in December 1974, camping out in the basement utility room, applied to Iowa, and proceeded to land three part-time jobs – working the grill at George’s Chili King on Hickman Road, clerking at an Iowa State Liquor Store on Douglas Avenue, and tending bar at Christopher’s, a family-owned Italian restaurant in the Beaverdale neighborhood. I worked until June, until I had enough money for my first year’s tuition, and then quit all three jobs and took off to Ann Arbor to find out what my good friend Jim “Prch” Prchlik was up to. He was sharing a rambling farmhouse on the edge of the city and making bank by working weekend shifts at the nearby Ford Truck plant. During the week we’d work in the garden and then roll into town to hang out with the street people living on and around The Diag and State Street.

Notable among this shifting lineup of characters were Tom and Whiskey Stone, members of a group of wandering souls who a few years earlier in an encampment outside Austin, Texas, had sworn an oath binding them as the Stone Family.[1] These folks helped me master the arts of panhandling and dumpster diving, not essential life skills for me but part of some socioeconomic experiment: Was it possible to live off the wastefulness and affluence of bourgeois America?

After a few weeks in Ann Arbor, I headed to Iowa City to scope out a place to live that fall. I have a distinct memory of coming into town on a sunny afternoon, walking down Iowa Avenue and noticing the C.O.D. Steam Laundry, a combination deli, bar, and music venue. When I heard The Grateful Dead’s “Truckin’” playing on the sound system, I knew I’d found a home. The inimitable and venerable Gerry Stevenson – in his usual garb of khaki shorts and long-sleeved Oxford shirt, glasses tipped on the end of his nose – served me a beer and a sandwich loaded with alfalfa sprouts.

I spent a couple days scouring the want ads, tracking down leads, knocking on doors, and returning to City Park each night to camp out. I’d found Stone Soup Restaurant and would wash dishes for a free lunch. One of the other dishwashers, Tom Leverett, invited me to a birthday party for Kevin Kelso, who worked at New Pioneer Co-op. Early that evening, I was panhandling spare change for, as I readily explained, a bottle of wine to take to a party. I was standing on the corner of Linn Street and Iowa Avenue, in front of Best Steak House, a restaurant run by two Greek brothers,[2] when my liquor store co-worker friend and his girlfriend Laura knocked on the restaurant window and gestured to come inside and join them. I ended up at a party at Laura’s house that night instead.

I did find a place that fit my budget of under $100 a month rent: a room above a Montessori pre-school on Reno Street with access to the kitchen used by the staff. I liked that it was a good twenty-minute walk from campus, and much closer to Hickory Hill, a large rambling urban park. I came to enjoy that walk home via the back alleys of the Goosetown neighborhood originally settled by Czech immigrants, admiring the tidy backyard gardens and grape arbors.

Across the hall lived the poet John Sjoberg and his cat Liz. John’s door was always open to me, and he became a valuable mentor. In the center of his room sat a typewriter with a roll of teletype paper cascading from it. I could always stop in and read where he had gone in his mind the night before. He was a poet of imagination and love. For example, here’s the opening stanza of his poem “Porch Window”:[3]

my head is green

the songs here, the bird songs

here & here & here

are my heart.

John introduced me to a group of poets, most of whom had graduated from the Writers’ Workshop and settled in the Iowa City area: Allen and Cinda Kornblum, Morty Sklar, Chuck Miller, Dave Morice, Jim Mulac. There was usually a reading on Friday or Saturday night at Alandoni’s Used Book Store at 610 South Dubuque Street,[4] and a party afterward. They called themselves Actualists, a name I always considered facetiously applied but one that recognized a supportive community of writers. The ambiguity of the name allowed room for anyone to fit in, including me, at least five to ten years younger than these other writers.

This decision, along with the decision, within a month after starting school, to take a job working part-time nights at the Stone Soup Restaurant’s bakery, established my roots in two Iowa City communities only loosely connected to the university, roots that made this start to feel like home, a place where I could “sit down and patch my bones.”

Having arranged to move into my place on Reno Street on the first of September, I took off for Madison, crashing a few days in an empty room in a large frat house reinvented as communal housing, and then looped back to Ann Arbor. A week later, Prch suggested I check out the Rainbow Gathering, an annual counterculture festival illegally held on some remote public lands the week of the Fourth of July. According to word on the street, it was happening near Hot Springs, Arkansas, that year. So I “got out of the door and lit out and looked all around.” In northern Arkansas I caught a ride from a NASCAR wannabe going 125 miles an hour down I-55, lakes becoming blurry blue visions, streaks of billboard boastings, flickering fenceposts and rows of cotton. Sporting a burning grin and waving his cigarette at me, he yelled above the noise, “Hot damn! Tomorrow’s our country’s birthday! Let’s torque it up in her honor!” I smiled weakly and held on.

When I got into Hot Springs, I could find no hint of the Gathering. I walked around, looking for anyone letting their freak flag fly who might be able to slip me the secret directions. Nothing. It turned out the Rainbow Gathering was in the Ozark National Forest[5] near Mountain Home, Arkansas, almost 200 miles due north, but I wouldn’t learn that until much later. I got dinner in town and spent the night on the outskirts of Hot Springs, near the road I came in on. Next morning, the Fourth of July, I got a ride from a couple of Arkansas Baptist College football players on their way to a party in Little Rock. They invited me to join their celebration.

When we got to the party, held in an apartment building owned by a team booster, I was goodnaturedly introduced to him and the other football players and their girlfriends as “Yankee.” There was a watermelon loaded with vodka and a tub of Budweisers on ice. Early afternoon, with only a breakfast in my belly, the drinking commenced. I somehow felt the need to defend the Union by keeping pace with these Little Rock secessionists. I lasted a couple of hours, eventually accepting defeat by diving into the apartment building’s pool with my clothes on. My friendly rivals fished me out and helped me to an empty apartment where I could sleep it off. They woke me in the morning, treated me to a hearty breakfast at a local diner, and sent me on my way.

Back on the road, I watched a long slow freight train pulling out of Little Rock. I decided to hop it, but by the time I got to the tracks, its speed had picked up. Running with a backpack on a rocky uneven railroad bed and trying to catch an open boxcar proved a failure. I picked myself up, washed off my scrapes, and proceeded to hitch to Bowling Green, Kentucky, where my friend Pat Berkowetz tended my wounds, physical and otherwise. I then stopped in Akron to see some high school chums before landing back in Ann Arbor. But I was soon back on the road, hitching to Minneapolis with Kelly, and continuing on my own, west to Seattle, down to Oregon and San Francisco, back up to Ashland, Oregon, east to Denver, and finally Iowa City by the end of August.[6]

1975 was a restless year. Like many young Americans, I was searching for something I could trust to be true.[7] When I moved into the room above the Montessori school and started classes that fall, it felt right, like the satisfying sound of a puzzle piece clicking into place. I began to see the possibilities of finding my niche in this Midwestern college town – among a group of poets collaborating, engaging with the world, and celebrating whatever felt real, and among a community of folks creating a cooperative network to offer food that was natural, organic, unspoiled by the corporate world. For all the miles of wandering still ahead of me, perhaps I’d found a fit, a home, a place and people I could return to when I needed a rest.

Footnotes:

[1] For a photo of the three of us, see my blog post Friends of the Devil, Part 2. The daughter of an oil millionaire from Odessa Texas, Whiskey was a high school cheerleader impregnated by the star football player. After her dad denounced her and got a court order granting him sole custody of the child, Whiskey hit the road.

[2] Who would respond to every order by asking, “You want fries with that?”

[3] From John’s book Hazel and Other Poems, published by Allan and Cinda Kornblum’s Toothpaste Press in 1976. His inscription in my copy: “To Dave & the House. May Kentucky always grow in your heart an’ help your head.”

[4] One of the 150-year-old cottages demolished in 2015 over the objections of historic preservationists.

[5] Video trigger warning: hippie nudity.

[6] I described some of the events of this part of the trip in my blog post The Art of Hitchhiking.

[7] The Pentagon Papers (1971) and the Watergate Scandal (1972-74) were just two manifestations of that sense of being betrayed.

People We Used To Be, Part 2

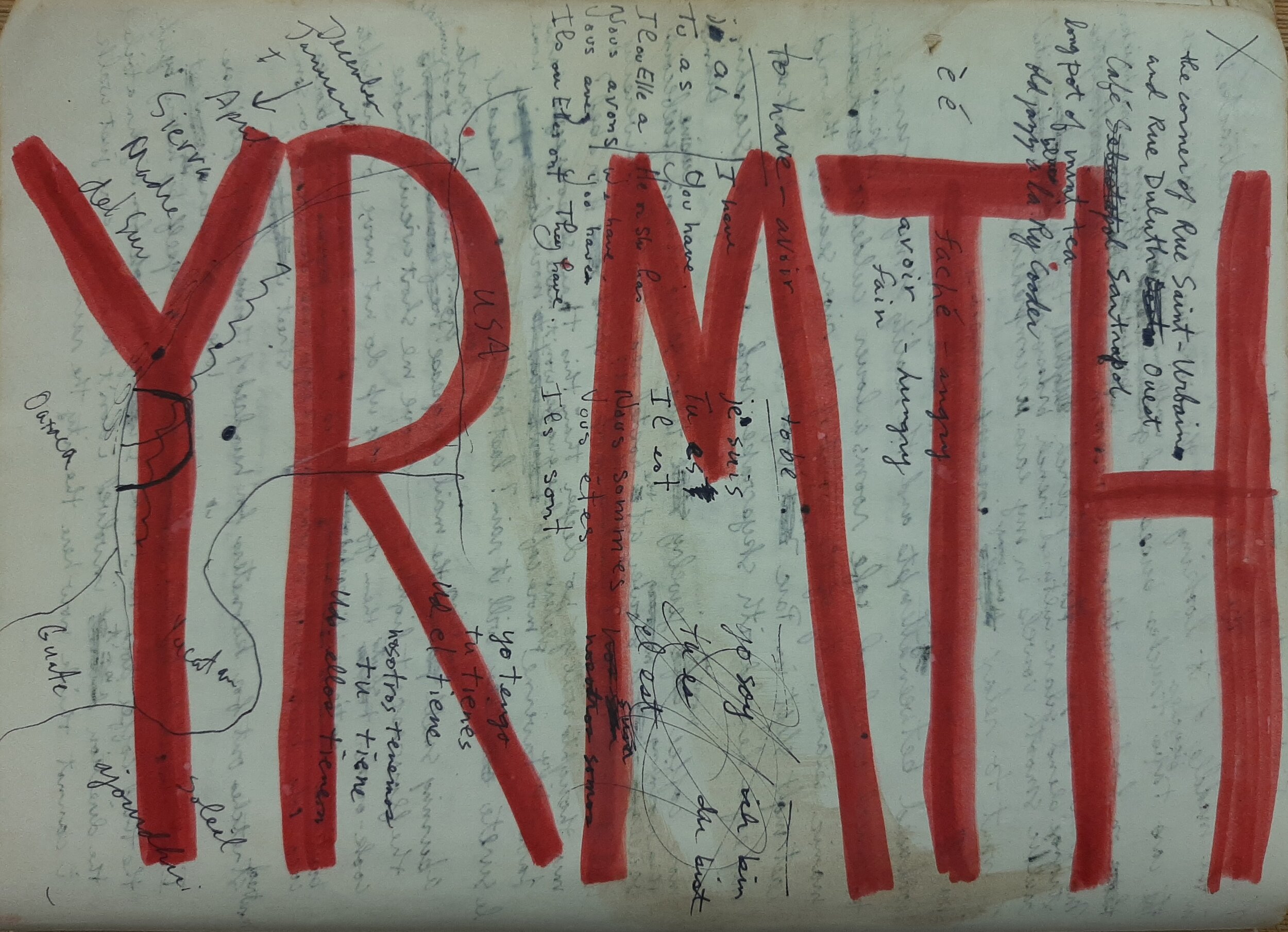

Hitchhiking sign for Yarmouth, from my comp notebook. In the underlayer of text, the conjugation of avoir and etre, most of it in Johanne’s hand. I must’ve been driving.

“Perhaps a person can write about things only when she is no longer the person who experienced them, and that transition is not yet complete. In this sense, a conversion narrative is built into every autobiography; the writer purports to be the one who remembers, who saw, who did, who felt, but the writer is no longer that person. In writing things down, she is reborn.” -Rachel Kushner, “The Hard Crowd: Coming of Age on the Streets of San Francisco”

Bidding farewell to my new friends Johanne and Marc and their cabin in the woods near Mont-Joli, I headed southeast on Highway 132 toward New Brunswick. As I passed through the little eastern Québec towns – Sainte-Flavie, Sainte-Angèle-de-Mérici, Saint-Antoine-de-Padoue[1], Sainte-Jeanne-d’Arc, Saint-Noël, Saint-Alexandre-des-Lacs, Sainte-Florence, Saint-François-d’Assise – I thought about the communion of saints, the mystical bond uniting us through hope and love. Was this what I would learn on this journey into the unknown?

When I crossed into New Brunswick, I entered the Maritimes, Canada’s Atlantic coast provinces, originally the home of the Mi’kmaq, Maliseet, and Passamaquoddy people, taken over in the early 17th century by British and French settlers. The French settlements were known collectively as Acadie. And my route along the New Brunswick coast – Highway 11 – had been named the Acadian Trail. The rides were short but came as quickly as I desired them to, and the entire southeasterly route from the Québec border through New Brunswick was less than 400 kilometers. As I traveled I could make out Prince Edward Island, ten miles across the Northumberland Strait.

When I crossed into Nova Scotia, I picked up the Trans-Canada Highway again, heading due east and then crossing the narrow Strait of Canso separating Cape Breton Island from the rest of Nova Scotia. I picked up Highway 19, which took me along the northwestern side of the island. As the traffic thinned out and the little towns grew fewer and farther between, I slowed down, enthralled by the romance of the sea and landscape. Sheep grazed the high meadows of yellow clover and lavender, thickets of wild roses, huckleberries, raspberries, leading down to the fishing villages and plummeting into the Northumberland Strait.

A ride dropped me off midday in Margaree Harbour, a picturesque village at the mouth of the Margaree River. I walked around until I found the most popular café. Afterward, hiking across the bridge over the river and out of town, I burst into a spirited song of the road:

Hike a stiff easterly breeze

with a bellyful of fish chowder –

the trawler’s come home with the catch.

Fling yodels off the precipices,

echoing down through the dales.

String the Acadian fiddle, lads!

Blow ye winds on the bagpipes!

Near Chéticamp I entered Cape Breton Highlands National Park, 366 square miles of high plateau and rocky coastlines. No roads led into its heavily wooded interior, and the park contained a wealth of wildlife, including lynx, bobcat, moose, black bear, and coyote [2]. Following the Cabot Trail, the road circumnavigating the park, I pushed on to the Highlands, the cloud-hidden spruce, jackpine, and birch reaches through which the Chéticamp River cut a gorge.

Near MacKenzie Point, knowing that the route was about to turn east and inland along the northern boundary of the park, I stopped for the day. Because I hadn’t stocked up on enough provisions to allow for multi-day camping, and the handful of official park campgrounds offered only the most basic tent-camping amenities, I realized this might be the extent of my stay. I followed a short trail to an overlook, and then wandered off that trail for some tent-free camping. From my sojournal:

camp on high cliff overlooking

the Gulf of Saint Lawrence.

beyond that Newfoundland,

the Grand Banks,

the North Atlantic.

scrub pine for wind protection,

moss to cushion the bedrock.

quarter moon gives way to

milky stream of stars

to glistening blue sunrise.

Cabot Trail along the northwestern coast of Cape Breton Island

The next morning, I scrounged up a couple of apples and a hunk of cheese from my rucksack and sliced it all up for a little breakfast plate. I’d been on the road for almost twenty days and hitchhiked over 2,000 miles to arrive at this beautiful morning in this spectacular place. And that was it. That was all I needed or wanted from this trip. From that point on, I was moving in the direction home – across to the eastern side of the island and then south along the coast. I was packing Gary Snyder’s Turtle Island in a pocket of my rucksack, reading and rereading his poems and essays. In “Four Changes,” I’d underlined: “Balance, harmony, humility, growth which is a mutual growth with Redwood and Quail; to be a good member of the great community of living creatures. True affluence in not needing anything.” After camping for the night on a beach, I wrote in my notebook:

driftwood and smooth beach stones

are ideal for campfire cooking.

boil brook water

add five hands

of rolled oats

stir until thick

mix in honey, raisins, sunflower seeds

rich helping of peanut butter.

this

will last until midafternoon.

After stepping off Cape Breton Island, I continued along the southeastern coast of Nova Scotia, small fishing ports anchored to the rugged coastline, interrupted by Halifax, the only substantial city in the province. The white horses of the surf raced along, the ocean tossing tangles of rigging and mislaid lobster traps on its shores. Big-boned gulls met up at the cannery docks after following the fishing trawlers home. Little fingers of the ocean curled up into the land, beckoning – Halifax Harbour, St. Margaret’s Bay. The land jutted out its chin where the storms broke and the wind never ceased – Fox Point, Western Head. Across the waves, a white-rocked beacon cast its lonely eye across the ocean, a mother searching for her son, lost, swept away.

I was traveling easily, unhurried, no schedule, no deadline, this time with myself. When I wanted a break from the road, the ocean was never far. Because of the Gulf Stream, the southeast coast of Nova Scotia offered bracing but pleasant waters for swimming:

still cove of rock

shelter from the sea’s turmoil.

cliffside coursing with pink granite

flecked with agate and quartz.

water transparent

twenty feet deep off this edge.

sea tern enters

circles

dives for its meal.

When I reached Yarmouth, at the southern end of Nova Scotia, I took my leave of the Maritimes. I booked passage on the ferry out of Yarmouth Sound, past the Cape Forchu lighthouse, across the Bay of Fundy as the evening fog rolled in – 180 kilometers to Bar Harbor, Maine. I roamed the ship, observing my fellow passengers, stopping at the bar for a Moosehead Ale and a shot of rye whisky. On the stern deck, I met two free-spirited women travelers from Minneapolis and kept their company for the rest of the voyage, sharing their cigarettes, drinking ales and conversing between blasts of the foghorn, falling in love with ballet-bodied, green-eyed Mary – but we kept it friendly. Listening for whale songs through the night, we disembarked at sunrise.

I had one stop to make on my way back home. After graduating from Iowa, my friend Tony Hoagland had moved to Ithaca to test the post-graduate waters of the writing program at Cornell. I took US Highway 2 through the backwoods of Maine and into New Hampshire. Early that afternoon, as I was passing through the White Mountains, ten miles north of Mount Washington, I came upon a cascading mountain stream beside the road. I asked the driver to pull over to let me out, and climbed the hillside, following the stream, until I came to a place where the water pooled beside large basking boulders out of sight of the road. I stripped down and floated in the cool, clear mountain water, high on the wonder of it all, thinking about Tony:

I reached up to draw

the pennyroyal from my ears.

Rushing back came the sound of water.

The river reclined on rock contours,

pocketfuls of coins laughing down its slope,

the sacred chords of silvery promises.

As I lingered, the sun dried thoughts of you on my skin.

One last border to fall before the flints of our souls will strike again.

I continued on Highway 2 into Vermont, then south on I-91 and west into New York State, reaching the Hudson River and Troy by nightfall. By then I was deep into this notion of an epic or mythic odyssey, and scribbled in my journal the next morning:

I’ve descended from the northern lights, where the stars streak with their weight to earth. There I watched the brazen criminal sun break through the granite chill. But last night I walked through the seven-storied ruins of Troy, and today I drift as sluggishly as dust across this valley. How will this compare with you – your movements swift and delicate, like the red fox?

I reached Ithaca that afternoon and spent a good couple days hanging out with Tony, talking about poets and poetry, getting high and swimming in Lake Cayuga. (Tony was always a great swimmer, and a member of that communion of saints.) Although as restless and footloose as I was, he was able to envision a life as a poet and teacher and work toward it. His focus was inspiring.

By the end of August I was back in Iowa City. Changes were in the works. My housemate Pat had given birth to a son, Sierra Soleil, in February. Like everyone in the house, I was helping raise him, but Pat and Sierra were moving to Santa Cruz to stay close to his father. I’d decided to not spend another winter living in the unheated attic of the Governor Street co-op house, and was about to move into the first-floor apartment of a house on Fairchild Street with Thomascyne, a feisty red-haired art student who would open doors and point me in new directions.

Footnotes

[1] When I was thirteen, I selected Anthony of Padua as my confirmation saint. I liked that he was the patron saint of lost causes, and that adding Anthony to my name made my initials D.E.A.D.

[2] In 2009, Taylor Mitchell, a young Canadian country singer, was attacked by coyotes on a trail near Chéticamp, and died from her wounds.

People We Used to Be, Part 1

A page from my composition notebook turned into a hitchhiking sign.

“I think we are well advised to keep on nodding terms with the people we used to be, whether we find them attractive company or not. Otherwise they turn up unannounced and surprise us, come hammering on the mind’s door at 4 a.m. of a bad night and demand to know who deserted them, who betrayed them, who is going to make amends.” –Joan Didion, Slouching Towards Bethlehem

When I returned to Iowa City in April 1977 after six months of traveling, I slowly eased back in. I was tending my co-op house’s back garden and occasionally helping out at the bakery – which had split off from Stone Soup and opened its own place a floor up in Center East as Morning Glory Bakery. But mostly I was chilling, digging the mellow summer vibe of Iowa City. Most of the students would vacate the premises, and cool, interesting folks just came out of the woodwork, or the woods. The day usually ended or started with drinks at The Deadwood or Gabe & Walker’s. A surprising number of good young jazz musicians were playing around town in various combos, before eventually splitting to the West Coast.

New Pioneer Co-op was preparing to move from its cozy second floor location on the corner of South Gilbert and Prentiss streets to a larger storefront beside Ralston Creek on South Van Buren. I was hired to help with the expansion, joining a staff that included my friends John, Sheila, Pam, Sue, and Bob. I learned a lot from those folks. We worked as a collective, sharing store decisions and duties, but as the junior member of the group, my usual role was supervising the volunteers, stocking the bins, running the cash register. I enjoyed the work, and the quality interactions with the co-op community.

I finally returned for my second year at the university in the fall of 1978. I had decided to work toward a General Studies degree, a liberal arts path that was actually an array of intersecting paths. My coursework was spread across a range of disciplines, an approach that felt natural. English Lit and Creative Writing, Film Study and Production, Languages (Spanish, French, Italian), Anthropology, Geography, Art History, Botany, Jazz Dance – I was omnivorous, helping myself to the buffet of knowledge.

By spring break, I was antsy. Iowa in March was barely thawing to a grey slush; one would need to head south to experience spring. I ignored that pull, deciding to visit my baking buddy Nancy, who had moved to a commune in Magog, Québec. As was often the case, I failed to clearly communicate the specifics of my visit. When I arrived on a frigid snowy night and called Nancy, she apologized that the community was in a spiritual retreat of sorts and couldn’t accept visitors right then. She did give me an address in Montréal. With few sleeping options that night, I went to La Régie de Police in Magog and asked to spend the night in a jail cell. They were cool with that request, but did lock the cell door.

The address from Nancy led me to a three-story brownstone in Old Montreal, a “spirituality centre” run by a Buddhist Jesuit (or a Jesuit Buddhist). I meditated with him, sitting zazen, quietly walking up and down stairs in my stocking feet, settling into my silence. I slipped out to see the city once or twice, but it was bitterly cold and I had little money. That's how I spent my spring break.

In July, after taking a Poetry Workshop class with the gracious Marvin Bell, I returned to Canada. Similar to Mexico, it was an inexpensive destination that offered a chance to cross boundaries and see new places. For some reason, Cape Breton in Nova Scotia had become a goal. Perhaps I was thinking of Herman Melville’s comment: “Nothing will content [humankind] but the extremest limit of the land.”

I headed northwest on US 151 toward Wisconsin, stopping along the way at New Melleray Abbey, near Peosta, Iowa. Passing through the oak doors of the Trappist monastery, I explained to a young monk, “I had a need for shelter.” Without a word, he pulled from the folds of his robe a small black copy of the New Testament and Psalms and placed it in my speechless hands. I stayed in a private cell (kept unlocked), joining the two dozen monks in the chapel as they chanted the prayers of lauds at dawn and vespers at sunset. They shared their vegetarian meals with me, made with produce from their gardens - excellent bread and sparse conversation. After two days of peace, I thanked them for their goodwill and continued on my way.

I stopped in Madison to see what was happening, because something always was. I hooked up with a couple other vagabonds, and a spontaneous party ensued alfresco. When we had exhausted every prospect, we started to think about a place to crash – we laid out our sleeping bags in a wooded thicket beside Lake Mendota, not far from the student union. Campus cops rousted us a few hours later, telling us we couldn’t sleep there and checking our IDs. For some reason, they could not confirm my identity in their database, which pleased me to no end.

I continued northeast through Wisconsin and into the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. It was quiet, uneventful traveling, a time for contemplation. While waiting for a ride, I wrote in my notebook:

Beside the road i’m following:

ferns, buttercups, queen anne’s lace,

ace of clubs with one corner torn off,

indian paintbrushes, black-eyed susans,

curls of birch bark, grocery lists,

scraps of maps, a lake, water

lilies, merganser diving.

Coming down through the Lower Peninsula, I stopped in Ann Arbor to get an energy charge from my old traveling companion Prch, and then on to Detroit to cross the Ambassador Bridge into Windsor, Ontario. I got a ride from a young Black guy going to visit his father in a Windsor hospital. But the border official, noticing my rucksack, asked me about my plans. I told him I was thinking of going to Nova Scotia and would probably be in Canada a couple weeks. I was directed to the Office of Immigration, where I filled out a form and was then told I’d need to have $25 per day and a bus or train ticket to my destination. That amount of money would usually last me a week. After being sent back across the bridge, I walked downtown to the Detroit-Windsor tunnel, where I caught a shuttle bus to Canada, telling a completely different story that time.

I followed King’s Highway 401 through Ontario and into Quebec, along the north shore of Lakes Erie and Ontario, and then the Saint Lawrence Seaway to Montréal. I did some urban camping in Mount Royal Park, big enough that one could keep a low profile and not be hassled. From that same “sojournal”:

The corner of Rue Saint-Urbain

and Avenue Duluth Ouest

Café Santropol

in Montréal

a bay window

large pot of mint tea

old blues and jazz in the air

I make a sandwich

cheese tomato bread

and partake

Leaving Montréal, I picked up the Trans-Canada Highway going northeast along the seaway. I got a ride from Johanne, a young Québécois woman. She soon picked up two more hitchhikers, who proved to be borderline assholes, to the extent that I was becoming concerned for Johanne’s well-being, but they soon reached their destination. She was on her way to visit her friend Marc, who lived near Mont-Joli, a fortuitous 500-kilometer ride. To pass the time, I asked her to teach me some French. As we talked, I became charmed by her smile and laid-back style. Yes, I wanted to travel with her and wanted to travel blind. Later on my trip, with her in mind, I wrote:

Your eyes are bluebirds

Flying from the forest of your lashes.

Your hair is chestnut straw

Where white daisies make their home.

Your skin’s a creamy yoghurt with honey freckles.

The Saint-Laurent wraps you in its blue blouse.

Your breasts are river-worn stones,

A truth humbling Rubens and the masters.

We talk as we follow the river,

Your hands rippling and fluttering in rhyme.

I learn from you: je suis, tu es, nous sommes,

New ways of saying the world.

It was dark when we got to Mont-Joli. Johanne invited me to spend the night at her friend’s house. Marc was a burly bearded Québécois brother living in the backwoods and subsisting on a large garden and a small herd of goats. He lived in a one-room cabin, but gregarious and generous, he heartily welcomed me. It was a cozy scene. Marc and Johanne shared the bed and I rolled out my sleeping bag on the floor nearby. Early next morning, they quietly made love, thinking I was still asleep. When Marc got up to milk and feed his goats, Johanne beckoned to me to join her in bed. During my travels, I met people like her who were, by their nature, able to carry others’ weight, lightening their loads.

Later that morning the three of us hiked to a nearby lake for a swim. As Johanne ran ahead, Marc turned to me, grinned, and said, “She is an extraordinary woman.” I smiled and nodded in agreement.

Going Down to Mexico, Part 6

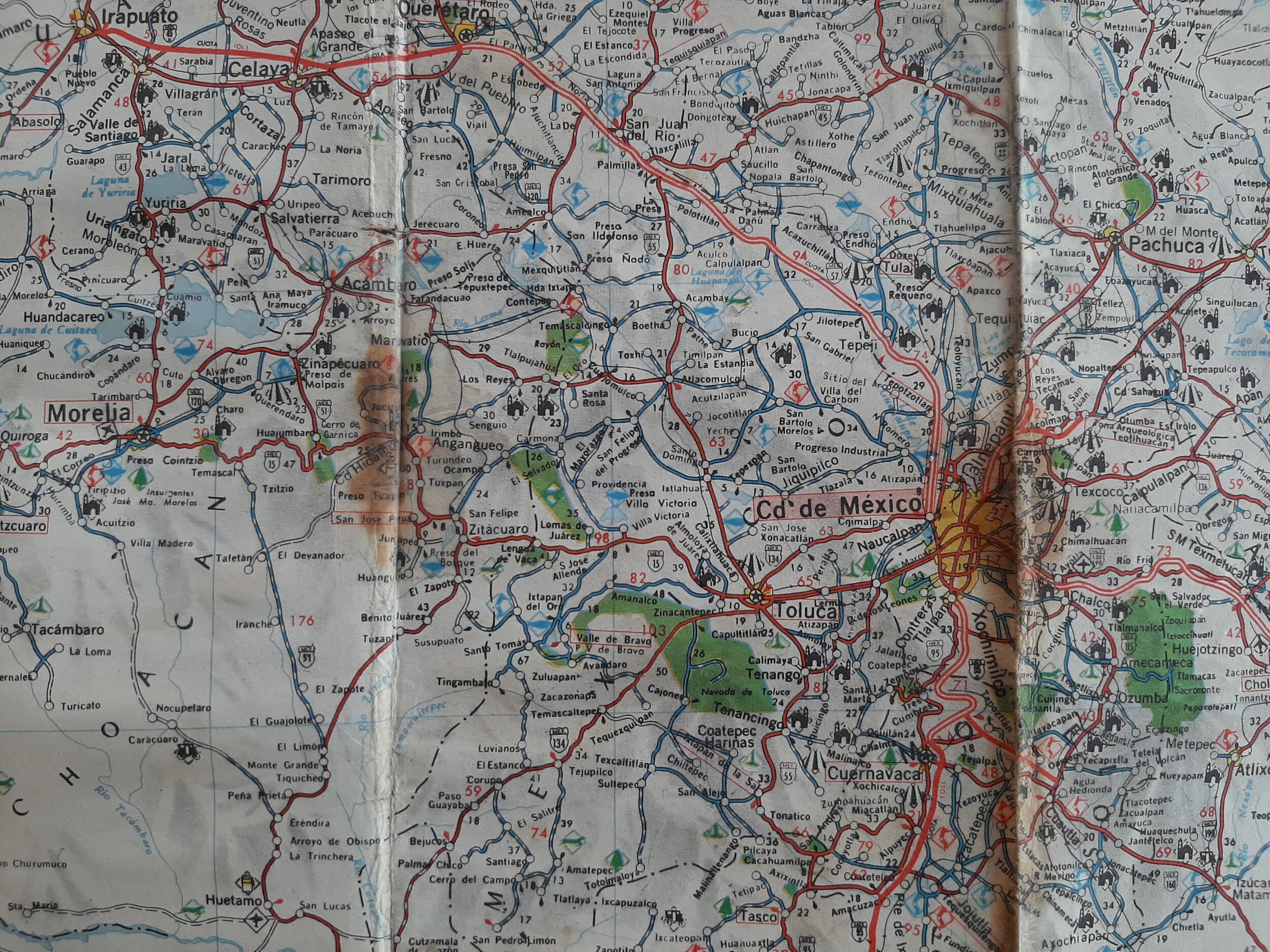

The route from Ciudad de México to Morelia represents the first 15% of the 2,100 kilometers I traveled in this last installment to return to the U.S. This is the trusty road map I used in 1976-77 and 1980, in the days before Google Maps.

“Really to see the sun rise or go down every day, so to relate ourselves to a universal fact, would preserve us sane forever.” –Thoreau

I left Ciudad de México and its twelve million inhabitants on February 22. Because of my backpack, I couldn’t take the Metro, but a confusing bus ride and some hiking eventually got me to Highway 15, the main road heading west. I quickly hitched a ride from three estudiantes taking a day off from book-learning and going to Toluca. They took me to the Calixtlahuaca ruins just north of the city, and we explored the stone pyramids for an hour before they dropped me off on the western edge of the city. Just as I was about to give up on hitching, two guys going to Guanajuato stopped, and we traveled through the late afternoon pine forest mountains. As we crossed into Michoacán and the sun was setting, I said, “¡Alto aqui!” and climbed a hillside into woods until I found a level spot and rigged up a shelter from the hail that came not long after.

I started hiking the next morning in the clear mountain air, but soon got a lift from a busdriver, and off we went to Zitácuaro, the bus filling along the way with indigenous Mazahuas, the women identifiable by their beautifully embroidered blouses and layered skirts. I bought bananas at the market and my favorite treat, calabaza dulce, from a street vendor and walked to the edge of town. A friendly couple soon stopped and took me fifty kilometers to Ciudad Hidalgo. Noticing a marker on my map for an agua termal, Los Azufres, I hiked five kilometers to the turnoff and then grabbed a bouncing twenty-kilometer ride in the back of a pickup up a logging road to a blue lake fed by a hot mineral spring. I set up camp on the far side of the lake and dove into the bone-chilling water. The first campfire I’d made in a while warded off the mountain night chill.

In the morning, I found the hot spring by following the rotten-egg smell of sulfur (azufre) to its source. A simple setup corralled the spring in a four-foot-deep pool, the overflow spilling into the lake, so one could comfortably steep in 90-degree water. I shared this delicious pleasure with one family, soaking for over two hours, luxuriating and exfoliating.

Next day, a couple of quick rides took me to Morelia, where I stopped for lunch and stocked up on fruit, veggies, and eggs, and then camped on its outskirts at the edge of a cornfield. In the morning, the first passing car stopped to pick me up, two young guys just returned from a year in Chicago. I decided to stop in Zamora for lunch, checking out the city and treating myself to their famous chongos zamoranos. Then three men en route to Guadalajara gave me a lift in the back of their pickup. As we passed along the southern shore of Lago Chapala in the late afternoon, I tapped on the top of the cab to stop, clambered out, and found a spot beside a stream at the edge of a strawberry field – laundry day at the lakeshore, sweet juicy fresas for breakfast (and lunch and dinner).

After a three-day break, I was back on the road, a couple of rides taking me to Guadalajara. I eventually wandered into a plaza where lots of handsome young kids were setting up a stage, so I stayed late to enjoy a ballet performance. I found a church and sought out the priest to ask for a place to sleep. He filled my need by taking me to the Civil Hospital Alcalde, where I slept in a spare bed in the men’s ward. In the morning a nurse placed a glass of milk on the bedside table like a votive candle.

I was now moving steadily, not in a rush but making miles most every day. I hitched a ride from a young couple and their two sons traveling from Mexico City to Puerto Vallarta. So, across Jalisco and into the dry rugged mountains of Nayarit until our paths diverged near Avakatlan. The next morning, a well-dressed elderly man stopped to give me a lift. He spoke good English, and I sensed this was an opportunity to share the message. He listened intently and then offered that he too was a seeker and had found his answer in Kirpal Singh, master of a spiritual practice known as Yoga of the Sound Current. We stopped in Tepic, the capital of Nayarit, and he treated me to brunch at the Hotel Junipero Serra, where I enjoyed enchiladas verdes on a veranda overlooking the city, my fanciest meal in Mexico. He was on his way to Culiacán but diverted from his route to visit the fishing port and surfing town of San Blas, and I tagged along. I thought about staying a few days but had a difficult night camping in a palm grove near the beach, where I was attacked by mosquitoes and sand fleas.

In the morning I moved on, a short hike and then a ride back to Highway 15, now heading northwest. Crossing the Río San Pedro, I decided to stop for a swim to wash off the heat, dust, and sand flea memories. I crossed the bridge and hiked upriver a kilometer, stripped down to my shorts and, in my excitement to cool off, dove from a six-foot bank into four feet of water. Luckily, the bottom was muddy, but it was a hell of a jolt that dazed me and left me stiff and sore for days – from my head and jaw down my spine. My mother always displayed on the wall by our dining room table a small framed picture of an attentive guardian angel hovering near a boy and girl at the edge of a cliff. Was that the spirit that saved me? I rested up and recovered for a day, visiting the nearby pueblo and catching a glimpse of some of the reclusive Huichol people who live in the nearby mountains.

The next day I caught a ride from a semi driver, a thoughtful hombre into writing and philosophy and Kahlil Gibran. We made a connection and I shared the message with him. He dropped me off on the outskirts of the tourist city of Mazatlán, where I wandered through quiet Sunday afternoon streets and down to a stone jetty away from the busy beach hustle to watch the waves break and the sun set on the ocean.

The land was becoming increasingly arid as I continued north. A ride into Culiacán, the capital of Sinaloa and the pre-cartel Mexican drug business, a city with more flashy cars per capita than any other in Mexico. I stopped in a plaza for a lunch of fruit and chatted with a law student. A long walk to the outskirts of the city, a long wait, and finally a short hitch to a naranjal, where I camped that night under the fragrance of orange blossoms. After oranges for breakfast, I stuffed my backpack with a dozen more.

My second hitch of the day, from a friendly taxi driver and shrimper, took me to Los Mochis. He invited me to his home for comida (the main afternoon meal, as is Mexican custom) with his whole family – his wife making bread, son and pretty daughter-in-law, 84-year-old father-in-law, brother. Mucho platicando – lively discussion of life in Mexico versus Estados Unidos. Afterward, he dropped me off downtown. Two days of steady hitching took me another 650 kilometers north into Sonora. My last night in Mexico, I camped at a water reservoir on the outskirts of Hermosillo, celebrating by baking a banana-chocolate cake in a pan over my campfire coals. From my journal:

the dry places

the Sonoran Desert

the wind comes

slipping over the hills like a hawk

hot iguana sun and saguaro statues

in the stillness of the coyote darkness

a sky of glittering diamonds

spirits lose their power

At the end of over 4½ months in Mexico, I took a bus to the frontera, retracing the route of my brief excursion into Mexico two years earlier, the same blind boy playing harmonica for change outside a dusty bus stop diner. His playing had not improved. I crossed the border from Nogales, Sonora, to Nogales, Arizona, like going through some cultural time-warp, except we all were alike in so many more ways than we were different that the differences were insignificant.

I caught a lift from a Mexican American going to Tucson after visiting his dentist across the border. He also picked up Dean, a scruffy young hitchhiker from Indiana, and we headed north on I-19, him drinking tequila as the novacaine was wearing off. I volunteered to drive because he was weaving badly, but he turned me down. As we came up on two Arizona state patrol cars pulled off the shoulder to make a stop, I warned our driver to “maintain.” He did, by slowing down to twenty miles an hour, and still almost took off the driver side door of one of the patrol cars. We were nabbed a few miles down the road, or he was nabbed, drunk, with no car registration and a trunkload of suspicious mag wheels. Dean and I got our IDs checked and our rucksacks sniffed by drug dogs and told to walk to the next exit ramp.

When I got to Tucson, I called Iowa City, nervous with anticipation, and talked with Pat. It was a happy long-distance homecoming, tempered by the news that she had miscarried back in the winter. I was surprised how good it felt to talk with a friend, someone from my household, someone whom I’d worked beside many nights in the bakery. This, I realized, was my home (or home base), my family, all that made the journey meaningful. Pat was heading to California to visit family and friends, so we made plans to meet in Santa Clara in a week.

I took my time hitching up the coast. On the vernal equinox, I camped with a Dutch macrobiotic cook named Biek and another hitcher in a Big Sur meadow, waking at sunrise in a field of California poppies. Pat and I met up later that day, a sweet comfortable reunion. We hung out in Santa Cruz for a week and then hitched back to Iowa City. During those ten days together, our friendship deepened to something that would develop into the foundation for our marriage, four years later.

Back in Iowa City, I barely knew how to talk about this six-month journey. What happened to Michael, and all the others whose paths I crossed? I didn’t have a good answer to the question Dylan posed in the song he wrote when he was twenty-one years old: “Where have you been, my blue-eyed son?” Perhaps I’m only now beginning to “learn my song well.” My last journal entry ended:

April 1st we return to Iowa City / the end of a lot of miles / i’m here now and something’s going to happen but i know not what / wait to hear from Prch in Ann Arbor back from his travels / think about Naropa, the Rainbow Gathering, Cheryl in Vermont, other places or things to do here in Iowa City – the house, the garden, friends on nearby farms, poetry, Stone Soup, some job or another, connections getting rewired / i’m waiting

Glossary

chongos zamoranos - a sweetened milk curd dessert flavored with cinnamon

naranjal - orange grove

Going Down to Mexico, Part 5

The interior of the Basílica de Nuestra Señora de la Soledad (Our Lady of Solitude) in Oaxaca

As I reflect on this trip, I wrestle to explain the spiritual journey I was on. How did I come to share in Miguel’s mission to witness God’s love? How did I reach a point where I’d write at the end of a journal entry, “May the Lord be with me”? Like many kids my age (22), I was looking for answers. I was looking for a way to be at peace with myself and live in the world. The poet in me also relished, or was comfortable with, the mysterious and the mystical. Deep in my heart I knew this wasn’t the only path I would follow in my life, but it was the one presented to me at that moment, and I wasn’t going to be so stubborn as to refuse it.

Sunday, January 30, was our last day in Puerto Escondido, capped by the excitement of a school of sardines veering into the bay, glittering silvery as they leapt in the air, followed by larger fish and a flock of terns feeding on them. All the niños rushed down to the shore as sardines and other fish were beached or trapped in shallow pools. We followed them and grabbed dinner – a good-sized sea bass flopping on shore. The next morning we got a ride to San Gabriel Mixtepec, about fifty kilometers north, in the back of a flatbed truck carrying spools of barbed wire. As the truck wound its way up a dirt road into the mountains, it took on other passengers – one with a pig, another with a portable corn miller, a family with two children – until the bed was full. Miguel and I slept that night by a stream under coffee trees.

The next day we got a late start, missing what little traffic there was, and hiked through pine forests, quiet cafetales, and crisp mountain air to the next town. We got a better start the following morning, and a ride from the first passing vehicle, a truck delivering tanks of cooking gas to towns along the way, up into the misty morning clouds, cresting the Sierra Madre del Sur, and down into the Central Valley to Sola de Vega, where the pavement began, and on to San Pablo Huixtepec, where we camped by an irrigation dam under a full moon. At the other end of the broad agricultural plain was the city of Oaxaca, thirty kilometers away.

One ride brought us to the edge of the city, and we hiked the last few kilometers, from the farms on the outskirts to el centro. We tested a seminary for a place to stay that night and were offered sixty pesos and directions to a hotel – our first bed and hot shower in months. Asking around for a camping spot the next day, we discovered a long set of stairs, twenty minutes from the Zócalo, that took us up a hill to an amphitheatre and beyond that a forest. We set up camp on Cerro del Fortín, from which we could look out over the city. In the morning we met the men who guarded the forest, protecting it from households seeking stove wood. They were friendly and let us store our rucksacks in their hut during the day.

Oaxaca offered lots to see and do. The Zapotec ruins at Monte Albán were a short bus ride away. The Museo de las Culturas de Oaxaca gave a good overview of the pre-Columbian Zapotec and Mixtec civilizations. We saw a French movie with Spanish subtitles at the French language school one day, went to a free classical guitar concert another, wandered the city, unwinding at times in one of the many beautiful churches, such as the aptly named Basílica de Nuestra Señora de la Soledad. We hung out at the Zócalo, scrutinizing the tourists and admiring the Zapotec women in their beautifully embroidered huipiles.

A huipil (traditional indigenous tunic) that Pat brought back from a trip to Oaxaca with her friend Sue Martinez in 1974

Every day we stopped at the mercado for a treat of fresh produce or large mugs of café con leche. In one of the small tiendas on the street side of the market, we met Señora Eugenia, who owned a mole shop. (The small containers of peanut butter she stocked first drew us in.) We were attracted to her charm and intelligence, and chatted with her when she wasn’t busy with customers. She sold us a jar of her mole negro and showed us how to use it to elevate a dish of arroz con pollo. Later we visited her home to help repair a chili roasting machine. In her factory, located across the inner courtyard from her residence, all the ingredients – cacao beans, peanuts, chili peppers, onions, garlic, and spices – were roasted, ground, and combined to make this Oaxacan speciality. The aromas and powdery dust merged and drifted in the sunshine slanting through the skylights.

We saw the forest guards only on weekends but got to know them well. We watched one skillfully weave a basket from strips of bamboo, and he let us try our hand at it. We shared our message with a number of them, talking about our experiences: “I once was lost but now I’m found.” Over time, this had become a natural thing to do, and in a country as religious as Mexico, people were receptive and respectful. It was never about proselytizing. I gravitated to the clarity and brevity of the Beatitudes: “Blessed are pure in heart, for they shall see God.”

Miguel and I returned to the issue of taking our separate paths, considering the pros and cons as we walked the city. Acknowledging our spiritual concordance, Miguel tentatively agreed to the proposal. More discussion was needed, but the tenor of the conversation was less heated than that of two months ago. I wanted to make sure the break was clean, positive, and above reproach.

We met two men who offered us information about magic mushrooms, which we’d been interested in since a conversation in Morelia. At their house they showed us photos of derrumbes: psilocybin mushrooms – ten centimeters tall, white stems, phallic black heads, growing in bunches in June and July near Huautla de Jiménez, a Mazatec pueblo about 200 kilometers north of Oaxaca. A strange and powerful mixture of mystical and drunken spirits resided in that house, but they listened intently to our message.

Near the end of our second week in Oaxaca, Miguel came down with a severe stomach flu. On the second day of his fever, he became incapacitated, and I busied myself caring for him. The fever tested Miguel, and in the middle of it he raised the issue of our imminent separation. He chastised me for being self-centered, a charge I couldn’t refute. During the coldest night we’d experienced in a long time, Miguel’s fever broke. The next morning I fixed a hearty breakfast of huevos rancheros (minus some of the chili peppers). As the sun warmed us, we became overpowered by the moment – the return of health and strength, the relief after an emotional trial – and we both realized it was time to part, that this would be a step forward.

That evening, Miguel and I shared a long farewell hug, two tall lanky blonde guys from Austria (well, my grandfather was), one difference being a decade of experience. I packed up my gear and walked to the station to catch the night train to Mexico City. As I waited for the train, I was tested by doubts. I felt the absence of Miguel; we’d been traveling partners for 4½ months after all. But my thoughts also turned to a promise I made to Pat the day I left Iowa City: to return by April 1.

The second class section was crowded, and I wasn’t able to sit down until our soldier guards detrained at midnight. I stretched out, covering myself with my old woolen serape as we moved through the mountain night, the names of Indian pueblos whispered into my dreams. As morning came we entered the Valle de México – irrigated farms became dirty factory sprawls became working class slums became the comparative wealth of el centro. Disembarking at Estación Buenavista, I wandered the area, getting my bearings, stopping for lunch in Parque Alameda, asking around about places to stay. I was directed to Colonia San Rafael, just west of the city’s historic center. Many of its early 20th century mansions had been converted into pensiónes. (See Alfonso Cuarón’s Roma, set in the early ’70s in a nearby neighborhood, to get the vibe.) A sign in a store led me to Serapio Rendon 39 and a tiny room for 25 pesos a day ($1.25) with kitchen privileges for a few pesos more – homey, with lots of families and children.

On Saturday I visited the Palacio de Bellas Artes and marveled at its Art Deco interior and the impressive murals by Diego Rivera, David Siquieros, Rufino Tamayo, and José Orozco. I took a bus to the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, the heart of the student protest movement, where I met a group of architecture students on break from class and talked with them about politics and the student massacre of eight years before. The next day I took the Metro to Parque Chapultepec and spent four hours wandering the magnificent Museo Nacional de Antropología and then strolled through the park:

Everyone goes to Chapultepec Park on Sunday

The Metro line is crammed with

A flood of refugees from the working week

Families lay out picnics on the grass

Babies cry and melt ice cream on their new outfits

Children romp through the gardens

And play futbol around the monuments

Young lovers couple on the sexual merry-go-round

The lonely are not alone

Some visit the zoo it’s so nice

Others evade the cages of despair

They rent boats and row in circles on the pond

For one hour feeding the ducks

Monday, I visited the newly completed Basílica de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe and witnessed the devotion of pilgrims coming from all parts of the country, crawling on their knees the last hundred yards over paving stones to her shrine to petition for help or health. Sitting in Parque Alameda and enjoying my lunch, I was invited to meet that evening with a class of students studying English. Perhaps I’d offer them the message. The city was interesting but too fast and cold and dirty. I was relaxing into traveling solo again, open to the world around me, maintaining a clear-eyed view of my actions.

Glossary

cafetales - Small-scale coffee farms found in Mexico primarily in the highlands of Oaxaca and Chiapas.

Zócalo - Central plaza or square. The Zócalo in Mexico City was built over the ceremonial center of the Aztec city of Tenochtitlan.

mole negro - A marinade sauce that can be traced back to the indigenous peoples of Central Mexico. It can transform a simple arroz con pollo (chicken and rice) dish. Because of its complex array of flavors and laborious preparation process, it’s often associated with celebrations and festivals.

Going Down to Mexico, Part 4

Playa Zicatela, just south of Puerto Escondido, Oaxaca

“Everything in Mexico tasted. Vivid garlic, cilantro, lime. The smells were vivid. Not the flowers, they didn’t smell at all. But the sea, the pleasant smell of decaying jungle.” –Lucia Berlin

We spent a week at our camp home on Playa Azul on the Michoacán coast. Three college students from Mexico City joined us for a few days. A steady trickle of visitors stopped by, bringing reefer to share, nimbly climbing the coconut palms, a knife in their teeth, to harvest cocos – a refreshing beverage in a green-husked goblet. The steep drop-off at the shore made this beach less popular with families and surfers, but the waves were fun and fierce for a novice body surfer. More than once I caught an incoming wave the same moment I was getting caught in the powerful backwash – it felt like 90 seconds in a washing machine.

On Christmas Eve we went to town after dinner and took in the final night of Las Posadas, Mary and Joseph in search of shelter, the piñatas of Navidad descending until Midnight Mass in the tiny packed church, where gaiety mixed with solemnity. This marked a growing accord between Michael and me, a new bond of partnership. We talked of the spirits – fear and anxiety, resentment and regret, self and egotism, attachment and addiction, depression and despair – that haunted us and held us back. One evening two young men walked into our camp, sat by our fire, offered us drugs we had to refuse, and then silently moved on. After they left, we looked at each other, unsettled by the aura of malevolence, and silently mouthed in unison: Demons. I wrote in my journal:

and if angels sing in my head

if spirits stand over me

but pass on by

how can these be told?

On December 27 we moved down the coast, stopping in Lázaro Cárdenas for supplies and then catching a ride from two San Diego surfers headed to their friends’ house for a meal. We were invited to join them, so across the Río Balsas into the state of Guerrero, and twenty kilometers more to the beach town of Petacalco, where we met Russell, Carmelo, Sharon, Jay, Fred, all transplanted from Cape Hatteras, seeking a higher consciousness and the clean waves at El Faro in Lázaro. They rented the house and land from their friend Santiago, growing papayas, bananas, tomatoes, and beans. We set up camp in a coconut grove behind their house, becoming involved in the community and its efforts to achieve enlightenment by letting go of fears and egos. After dinner we’d all get high and engage in intense discussions on how to “be here now.” We contributed what we could, but they were on their own path.

One day we took an excursion, paddling surfboards across the mouth of the Río Balsas to an island where Santiago’s father, Samuel, farmed a paradise guarded by royal palms rising seventy feet in the air. He tended fields of maíz, jícamas, papayas. He harvested calabazas and camotes and treated us to plates of them, enmielados (boiled in honey). On New Year’s Eve we tried marijuana tortillas, then dinner at the house of Diego and Felipe, two local fisherman friends, and then back to the house, where the scene was lost in reefer, tequila, and rock ’n’ roll. On Sunday we made dinner in gratitude for our friends’ hospitality – tempura vegetables, gorditos filled with fried veggies, sweet creamy atole for dessert.

When we left on Monday, we took on new names to symbolize our new commitment. Reflecting on our experiences at Petacalco, we resolved to abstain from reefer, feeling it might be blurring our focus. I was now Marcos, and Michael became Miguel – one of the freedoms of traveling, because no one is qualified to contest the “truth” of your life. A fifty-kilometer ride took us to the pueblo of Lagunillas, where we stocked up and set off on a seven-kilometer hike down a dirt road to Playa Troncones, recommended by our Petacalco friends. The next day, searching for shellfish in the rocky shallows among sea urchins and mussels, a rainbow of fish darting in and out among the rocks, I was tumbled by the surf, receiving cuts and sea urchin spines I’d later have to extract. That afternoon a fisherman gave us a small shark he’d hauled in, which we then shared with the farmer whose land we camped on. After Miguel figured out how to skin the shark with the tools at hand, we grilled steaks.

We stayed at Playa Troncones for four days, the mountains a blue shadow at our back, the sea shimmering before us, sunsets glowing through the palm trees. We obtained drinking water and eggs from the farmer we’d shared the shark with, all the cocos we wanted when he harvested the grove, a feast of oysters one day from a man who dove for them. The Father provided for us.

After hiking back to the highway, we caught a ride in the back of a pickup to Zihuatanejo, a resort town rimming a beautiful bay. A string of hotels along the beach, a marina where yachts of all types docked, beaches populated with rich Chilangos and English-speaking gringos of all stripes – Murricans, Canucks, Brits, Aussies. After slurping down a bowl of pozole at a street stand, we hiked away from town to the other side of the bay, where we camped by a house owned by an absentee American and cared for by the Mexican family living next door. We quickly became friends with the caretaker, who invited us to attend a meeting for worship with his family, my first experience with a Jehovah’s Witness service. On Monday we exchanged dollars for pesos and treated ourselves to a lunch of hot tortillas fresh from a tortillería, bananas, and crema de cacahuates (yup, peanut butter).

We continued southeast along the coast toward Acapulco. Within a hundred kilometers, we hopped off the road and hiked five kilometers to a spot beside a swift-running stream near the pueblo of Santa María. We camped on a sandbank by the stream and slowed down for a couple days, fasting, reading the Bible, lazing in the sun, slipping into the stream to cool off, comfortable in the stillness. I wrote in my journal:

Friday morning, we were back to the blacktop and sticking out our thumbs for Acapulco. We got one ride, then nothing for hours and miles until three vacationing students from Mexico City stopped to deliver us to six p.m. downtown Acapulco. We soon met Antonio and Francisco, kids living honestly on the beach. They led us to Playa Caleta, the only Acapulco beach one could sleep on. Near the mouth of the bay, far from the glitz of el centro, we’d sit in the relative quiet and comfort of hotel chairs and enjoy a late meal. At dawn, we’d rise as the workers rushed through straightening chairs and raking the beach. We checked out the city, the glaring contrasts of wealth and poverty, the tapestry and travesty of the tourist trade, and the humanity that exists in spite of that.

Los Ángeles de Acapulco

every Saturday

the children of Acapulco get a bath

and as evening comes

the plazas and calles

become filled with the perfume

of jabón and champú

from the anointed heads

of children at play

We had success at the Mexican Immigration office, extending our tourist visas for three more months. We enjoyed Acapulco beach life for the next few days, relaxing under the sombrillas when the chair-ticket guy was not around. Our little beach urchin friend Manuel would bring us leftovers from his daily hustle of the tourists – hot cakes and pastries in the morning, steak or fish and bolillos in the evening. We chatted with some of those tourists – a retired German diplomat, a restaurant owner from Blackpool, a retired British civil servant – but our patience was tested by overheard conversations that revealed how oblivious they were of the world around them. On Friday we took Manuel to a dentist to have his teeth looked at and bought food for the next leg of our trip.

The next morning we took a bus through the part of Acapulco we’d avoided – Pizza Hut, Shakey’s, Denny’s, Big Boy, Colonel Sanders – and then got a ride in the back of a camioneta climbing the cliffs overlooking the bay and then south. The road was quiet, but we caught a ride from a crazy young busdriver who burned through his route and then talked with us at its end, sharing his pan dulce. A traveling salesman took us to Pinotepa Nacional in Oaxaca, along the way turning off onto a dirt road to a beach restaurant and a delicious fish dinner. And finally to Puerto Escondido, a fishing port turned surfing and hippie hangout. We scoped out the town, full of hip young gringos, trailer park offering campsites for 17 pesos (85 cents) a night. We hiked down to Playa Zicatela and made a quiet camp in the scrub woods away from the beach. The surfers would come out our way to wrestle and ride the waves, the beach strewn with self-absorbed kids getting high or tan or both. We befriended a Belizean and Canadian couple who had met in Escondido. He was nursing a knife wound suffered at the hands of her enraged former boyfriend, but we admired how completely in love they were.

We decided to bid adiós to the coast and head north toward Oaxaca City, bypassing the Yucatán and Guatemala for now. Over three months in Mexico and four months on the road, we moved slowly but deliberately. Miguel and I still had our differences, but they were the healthy, normal consequences of traveling together. I was asking questions whose answers strengthened my convictions, eased my doubts, and filled me with peace and equanimity. My apprenticeship was coming to a close.

Glossary

Las Posadas - Literally, the inns. A nine-day reenactment of Mary and Joseph’s search for lodging, which ends on Christmas Eve. A popular processional ceremony in Mexico and other Latin American countries.

jícamas, calabazas, camotes - Jícamas and camotes are root crops. The jícama has a sweet, nutty flavor, crisp like a water chestnut. Camotes are in the sweet potato family. Calabazas are in the pumpkin family.

Chilangos - Residents of Mexico City or Mexico, DF (Distrito Federal). When used by those from other parts of Mexico, it can have a derogatory meaning. Citizens of Mexico City often use it as a point of pride.

pozole - A traditional Mexican stew of hominy and pork or chicken, often garnished with shredded lettuce, onions, garlic, chili peppers, avocados, and fresh lime juice.

Going Down to Mexico, Part 3

(Las Cascadas in Parque Tzararacua, Michoacán)

In San Luis Potosí, we bought train tickets to Morelia. Engine problems delayed our departure by three hours, so we missed our transfer. When we did arrive in Escobedo, a little pueblo in the state of Guanajuato, we disembarked to a brass band playing a fanfare. A couple dozen muchachos immediately swarmed us, as if the musical welcome were meant for us, while we inquired when the next train would depart … Not until the next morning. The kids followed us as we walked around town and finally to the Catholic church, María Auxiliadora (Mary the Helper), where we stopped to center ourselves and then talk with them until a Franciscan padre shooed them off. Because the night threatened rain, we asked for shelter, and he set us up in a house adjacent to the church, where we cooked dinner and bedded down on straw mats. The next morning, as we waited for the train, warming ourselves in the sun, we sat on a rusty steel girder stamped Krupp 1928.

That train took us 100 kilometers closer to Morelia. It also had engine troubles, so we missed the last train to Morelia. Acámbaro was a pretty little city tucked in among surrounding mountains. Sitting under the topiary orange trees of the main plaza, we were befriended by a group of muchachos who directed us to the restaurant with the best food and prices. Along the way, we lost one of our new friends when two plainclothes police rushed up, brutally grabbed him, and hustled him off because of some brawl he’d gotten into earlier. Young Mexicans would often gravitate toward us; I’m sure their motivations were various – but they were also simply curious. Sometimes, if they didn’t know or remember our names, they’d address us as maestros.

After our meal, we hiked out of the city and up into the hills, laying down our sleeping bags in a pile of corn stalks, burrowing in to shelter ourselves from the shower that occurred most nights. In the morning as campesinos passed on their way to the fields, I climbed the hillside and watched the sun illuminate the city’s white stucco buildings as it rose above the ridge behind me.

That day, we finally arrived in Morelia, the charming capital of Michoacán, known for its early colonial architecture, especially in el centro. On a recommendation, we made our way to the Seminario Santa María Guadalupe in the eastern hills of the city, and met a priest who gave us a tour and provided dinner and a place to stay at a nearby retreat house. After learning that was a one-night offer, we camped the next night in a half-finished restaurant.

When one of Michael’s pack straps broke, we found a zapatería and had all of our straps stitched up. Our rucksacks were usually loaded down with supplies: fruit and veggies, cooking oil and honey, rice and oats. Those rucksacks made us conspicuous but also helped us fit in. Men carrying home firewood on their backs, women carrying baskets of tortillas or produce on their heads – we each wore our burdens. Sitting in a plaza as evening approached, we met some jóvenes who took us to a houseful of partying students and musicians. We were invited to crash there as long as we wanted. Sometimes our needs were met in mysterious ways.

We spent almost a week in Morelia, going to a soccer match one day with our new friends. Another day I ran a gauntlet of Mexican functionaries in order to recover $200 of traveler’s cheques that had gone missing – federales, a public minister, local police, office of tourism, and finally a lower-ranking public minister who filled out my report – all so I could take it to the Banco de Comercio and then spend an hour on a repeatedly disconnecting phone call to Mexico City to get my refund.

At the mercado, we stocked up on groceries and plastic sheeting to expand our tent and then caught a bus to a park recommended by our friends, Parque Kilómetro 23, so named because it’s 23 kilometers east of Morelia. (If we had traveled 100 kilometers further, we could’ve entered the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve, except that scientists had just discovered this site the previous year.) After walking the confines of the park, we climbed a fence into a neighboring forest with more privacy. It was a good break from cities and travel – cows grazed the steep terrain of pines, firs, cacti, unfamiliar tropical trees, exuberant wildflowers, fantastic mosses. A man passed by to check the pines he was tapping for resin. We set up our camp on a thick bed of pine needles, and arose in the morning to a feast of fried macho plátanos drizzled with crema y miel. We discovered a stream in the next valley where we washed our clothes.

The nights were mountain chilly but the sun quickly warmed us. We sunned like frogs on large rocks beside the stream, reading the Bible and getting ourselves clear. We talked while stirring the embers of our evening campfire and got in touch with what was going on inside. I still had a lot of old shit to resolve and a lot of blanks to fill in on the questionnaire entitled “Who Am I?” Michael had been a valuable guide on this journey, but I still chafed at his insistence that I wholly commit to sharing the Father’s message. I wondered if we’d reached a fork in our paths.

That Saturday, we fasted on water, lemon juice, and honey, and discussed parting ways. I conceded that it should be a decision we mutually agreed upon. I slept half of that night and filled the rest with ruminations on love unhindered by expectations. Pat was on my mind – my Iowa City housemate and off-and-on lover, she was pregnant when I left. Although not the father, I planned to be there for her and her child.

The next day we caught a bus back to Morelia and stocked up at the mercado. December 12 is a national holiday in Mexico, el Día de la Virgen de Guadalupe, commemorating her visitation to the Chichimeca campesino Juan Diego in 1531. We wandered off to a nearby plaza, where we met José, who tried to sell us some mota. We went with him to the Bosque de Chapultepec, where we fell in with a group of stoners, got high, and then went to an outdoor concert. We crashed at José’s house that night, on the way stopping at a shrine for Nuestra Señora; we bowed our heads to pass under the folds of blue and white drapery adorning the path to her statue.

Monday afternoon we caught a bus out of Morelia to Quiroga, 45 kilometers west at the eastern end of Lago de Pátzcuaro. We camped on a hilltop overlooking the town and lake, in a garden of herbs and flowers. The chilly night kept the mosquitoes quiet, but by morning we were soaking up the sun’s vitamin D, sans clothing, until getting caught off-guard by a man and his son gathering herbs. By Wednesday we were moving on, hitching a ride in the back of a panel truck to Pátzcuaro, a popular tourist stop on the southeastern edge of that lake, known for its Spanish colonial and Purépecha indigenous cultures.

As we walked along the lake, looking for a campsite, we met some muchachos fishing and bought two lake trout from them for supper. We came upon a string of abandoned houses and moved into the last one. The next morning we caught a ride from a friendly truck driver transporting produce from Morelia to Apatzingán. He entertained us with stories about the area and his life as we swerved through the mountains. Sixty kilometers later, at his suggestion, he dropped us off at Parque Tzararacua, where the Río Cupatitzio descends in a series of cascadas. We hiked along the river to the bottom of a lush gorge, continuing to follow a trail into another valley, where a small cascada splashed into a deep blue pool. We set up camp, bathed, and made dinner. It felt like what I imagined paradise to be. Breathtaking flora frequently visited by hummingbirds. The sound of falling water merged with the melodies of songbirds. The days were warm and sunny; the nights were mild. Michael found another cascada upriver from our camp, a forty-foot drop that gave me a rush when I stood beneath its whoosh.

After four days there, we headed south toward the Pacific Coast. A man hauling goods from Uruapan to outlying towns stopped to give us a ride. I sat in the back of the truck with six boys grilling me with questions about los Estados Unidos. A series of short rides took us through tropical mountain forests, then cresting the Sierra Madre del Sur into a much drier climate, almost desert, and a long winding ride to a vista of the endlessly blue Pacific. When we arrived in Playa Azul, we hiked down the beach away from the sandy tiendas and restaurants to a grove of coconut palms sheltered from the sea breeze by bushes. We watched the sun set on the ocean in a blink and fell asleep as waves washed up on the beach.

The next day we went to Lazaro Cardenas, fifteen kilometers down the coast, to shop for supplies. We started off the day with a fresh papaya and a joint one of our new friends brought to share … and finished the day with a campfire dinner of spaghetti with marinara sauce and Swiss chard. At dawn the next day, Michael talked with the passing pescadores who fished the surf with nets, getting a promise of fresh fish for tomorrow, Christmas Eve.

Glossary

maestros - It's possible they were messing with us, but I’d like to think not. I felt honored to be called a teacher. It would take me 25 more years to officially become one.

jóvenes - Jóvenes are teenage kids, maybe early twenties. Muchachos are younger (tweens). Or at least, that’s how I used the words.

macho plátanos ... crema y miel - Slice up the plantain and fry in oil, both sides. The cream and honey add sweetness and make it a tasty breakfast dish.

cascadas - The river has a direction to go

down

over the edge into air and mist

cascading down in a white foamy roar

and again calm

onward

Going Down to Mexico, Part 2

(One of the prettiest parts of Tampico, Plaza de la Libertad, near the train station. Note the wrought-iron balconies on some of the buildings.)

Michael and I arrived in Tampico on Friday evening, October 29, and didn’t leave there until Saturday, November 27. Tampico is a fairly typical Mexican city – a mid-sized Gulf seaport, a little neglected since its oil boom days of the early twentieth century, far from the Gringo Trail – and that appealed to us. It seemed a good place to work on learning the language and culture of Mexico. We were given a place to roll out our sleeping bags in the church hall of the Iglesia Presbiteriana Jesucristo El Buen Pastor (Jesus Christ the Good Shepherd).

By this point in our journey, we had established a modus operandi when arriving in a new town. Michael saw himself as an apostle spreading the Good Word, following the instructions of Matthew 10: “Go to the lost sheep of the house of Israel. And as ye go, preach, saying, The kingdom of heaven is at hand…. Provide neither gold, nor silver, nor brass in your purses…. And into whatsoever town ye shall enter, enquire who in it is worthy; and there abide till ye go thence.” We would seek out a person, preferably a religious one, knowing they might be more receptive to our request. The conversation would go like this:

–Hello, can I help you?

–Yes, we have a need.

–What is it, my sons?

–We have a need for a place to sleep.

That was it. If they met our need, we’d gratefully accept the offer. If not, we’d “shake the dust off our feet.” I was the mostly silent sidekick in these transactions, occasionally called upon to translate because my Spanish was better. Michael was pushing me to become more than that, but I tried to explain that I couldn’t fake a calling. However, I wasn’t hearing anything in his message that troubled me. It was ecumenical and inclusive; if he was trying to convert anyone, it was to a life of love and spiritual wholeness. He and I were doing yoga, reading and discussing the Bible one day and books such as Herman Hesse’s Siddhartha the next.

We let the church congregation know we desired to stay in Tampico for a while. Michael wanted to work on his Spanish so he could share his message. We made our home in the church hall that week, buying pastries from a nearby panadería for breakfast, going to the mercado to choose from the wonderful array of fruit for our lunch – piñas, plátanos, naranjas, papayas, mangos, guayabas – each negotiation providing practice in Español. We’d find a bench in a plaza and eat our lunch while enjoying the lively parade of people and the wind rustling the stately palms overhead.

Manuel, a law student and the older son of the church pastor, took a friendly interest, offering us impromptu lecciones en Español. When he had free time, he’d introduce the city to us. We rowed a flat-bottomed boat across Laguna del Chairel and hung out with some of his friends, including Daniel, the son of the family who would eventually host us. Another day, we went down to the docks, boarded a Russian merchant ship, and were given a tour by an English-speaking officer, afterward drinking Brazilian beers with the sailors. On Todos los Santos (All Saints’ Day, or Halloween), we went to Playa Miramar and met a family who welcomed us to their three-room home, where we drank Carta Blancas and conversed about life in Mexico. The next day, el Día de los Muertos (All Souls’ Day), we visited a cemetery packed with people who had brought baskets full of flowers and food so they could tend and then picnic on the graves of their ancestors. It’s a major fiesta in Mexico.

Manuel also helped arrange a meeting with the Rodriguez family, who invited us to stay with them. Our second week in Tampico, we moved into a spare room in their home, becoming the center of attention, falling into the gentle teasing, the endless chistes, of a loving family – Mamá and her young adult children, Daniel, Estella, Chelly, and Estella’s niño, Sofía. The absence of Papá (Señor Juan) and Estella’s husband, Diego – working on Juan’s shrimper off the coast of Campeche – opened up room for us at the dinner table. Manuel stopped by on Saturday to take us across the Río Pánuco to a village in the state of Veracruz, where pigs roamed free in the grass-covered roads. We visited the home of his friend Olga, enjoying a simple feast of pescado, frijoles, arroz, tortillas. One night we happened upon a wedding reception and were invited to join the festivities and dance with the girls. We would accompany Estella and Chelly to the mercado to help with the shopping, learning where to find the best deals. Mamá taught me Sofía’s favorite lullaby, “Mi Muchachita de Corazón,” guaranteed to put her to sleep. And she showed us how to make empanadas: patting the balls of masa into thick tortillas, folding meat or cheese or vegetables into them, and frying them. Simple and delicious.

Sometimes life in Tampico got pretty intense, sleeping in a room adjoining a busy road, struggling to communicate in a second language, witnessing a tragic drowning in the river. The smells of the oil refineries wafting from Ciudad Madero, the bright red viscera and flesh of the carnicerías in the mercado, the noise and diesel exhaust of autobuses. The incessant discord of the street – taxis cursing, traffic police whistles screeching, bus drivers crossing themselves at each intersection as their brakes hissed, same as the men did from the plaza benches, “Ssssst, senorita!” A block from where we lived, a niña was struck and killed by a car. The next day, while we were on the roof fixing the TV antenna, we saw people gathering at the family’s house for the funeral.

When Señor Juan returned from Campeche, brimming with stories of shrimping in the Gulf, we knew it was soon time to move on. Michael and I took on a plumbing project to fix leaks in the two bathrooms; the experience of hunting around town for parts expanded our vocabulary and language skills. Our last Sunday with La Familia Rodriguez, we prepared a North American feast of spaghetti with a hearty marinara sauce and french fries, onion rings, a tossed salad, and a fruit salad for dessert. We had all grown close in the almost three weeks we lived there.